The Food of Ancient ROme

Many years ago, I read a book by historian Roy Strong, a book called FEAST: A HISTORY OF GRAND EATING. It contained one line about the ancient Roman gourmand Apicius and his death. It was so crazy that I thought I would write a scene about it, for inclusion in another book I was working on. Instead, I fell in love. With the era, with the food, with the world of ancient Rome. I wrote the story of Apicius, and I learned a million little things about dining in ancient Rome--and today I impart them to you.

Not Your Nonna's Italian Cuisine

When one thinks of Italian food, it's likely that the foods that have remained with us from ancient times are not those that come to the forefront of your mind. They didn't have pizza, pasta, tomatoes or lemons, and garlic was only used medicinally. Today we gape at some of the foods that the ancient Romans ate, foods that now seem quite bizarre to many of us, including fried dormice and flamingo tongues (and peacock and nightingale tongues). Many of these foods were consumed only by the very rich, whereas the average Roman citizen ate a simpler diet. The ancients were just as enamored with strange and rare foods as we are today. Other types of ancient Roman food that still remain with us today, including tapenade, quiche, and more.

Clearly, these dishes are not the same as we are familiar with when it comes to the world of Italian cooking today! And in fact, many of them are better known as dishes famous in other countries, such as haggis, now the national dish of Scotland, and foie gras, which the French perfected. That's because the Roman Empire was vast and when they conquered other countries and began settling in them, they brought their favorite foods along as well. Read on to find out more about these foods, and how wealthy ancient Romans were just as much into the culinary arts as we are today.

Table of Contents

.jpg)

Dining Habits

The Divide Between Rich and Poor

Just as today, there was a vast gap between the wealthy equestrian and patrician classes and the regular people of Rome, the plebians. They dined very differently and ate different foods.

The plebs primarily ate bread and vegetables, cheeses and if one could afford it, some meat. If you lived in the city it was more challenging because you likely lived in a wooden apartment building, often 5-6 stories high, called insulae. And if you lived in a wooden building, the chances of you firing up the stove on the second floor were zero. Which meant that you had to go out to get a hot meal. Fortunately, all over Rome there were a variety of food shops called popinae or thermopylae. They had counters with big vats called dolia, which stored foods that could be scooped up to a hungry traveler on the go. These shops usually had a stove to cook and boil meats and vegetables. Here is an example of a counter in a popina in Pompeii.

Many of these shops had rooms where people could also sit down and eat. Menus, such as the one in the photo below from a shop in Ostia Antica, were often painted directly on the wall. Typical dishes served included meatballs, lentils, fritters and other quick-to-make and easy-to-eat-on-the-go foods. It was not seemly for a wealthy person to dine at these shops and there are numerous accounts of patricians (and even emperors!) being derided for hanging out with the rabble. Plebians would not have eaten laying down, but sitting up just as we do today.

Dining in a wealthy household, on the other hand, would be a very different affair. If you were lucky enough to be a client of a wealthy patron you might receive a dinner invitation and a coveted spot on your patron's couch. You would be expected to bring your own napkin with you and when you arrived, you would give thanks to your host's household gods at the house's Lararium shrine. The dining room and the dining couch were both called a triclinium. The couch was three sided and usually accommodated nine diners, a number which represented the nine muses. If more tables were needed, additional tricliniums would be set up, but keeping a multiple of nine was desired. Diners would lay on their left side. The middle seat was the most coveted and important. Sometimes guests would bring along a friend who wasn't necessarily invited. This person was called a "shadow" or "parasite" and would sit at the foot of the guest who brought them. They were expected to bring witty banter and conversation with them to help compensate for their free meal.

The idea of three courses to a meal began in ancient Rome. You began with hors d’oeuvres (called a gustatio), the main course (mensae primae), and the dessert (mensae secundae). A typical meal usually began with an egg dish of some sort and ended with fruit.

A "scissor" slave would cut the meat and food up for the guests, who would use their right hand to take food from the center table. Sometimes they would use a spoon which had a pointed handle to spear the food, or to open up shellfish.

From Chapter 3 - Feast of Sorrow

Apicius and his guests chatted merrily, enjoying the cooling salt breezes, marveling at the pomegranate sunset over the ocean. A three-sided couch, or triclinium, held nine guests to represent the nine Muses, as tradition dictated. Each diner lay on his side propped up by one elbow. A square table rested at the center of the couch, laden with hard-boiled quail eggs, grapes, olives, and little treats to whet the appetite. The guest of honor that night, in unusual form, was a woman. She lay laughing in the coveted position on the far left of the middle couch, next to Apicius.

“Who is that?” I whispered to Rúan. I was grateful for his willingness to help me navigate the politics of Apicius’s household.

“Fannia, an old family friend of the Gavii. She recently remarried but you’ll not meet her husband anytime soon.”

I was about to ask why but Rúan continued, gesturing at the man who sat between Fannia and Apicius’s mother. “I don’t know the name of the man at the end of the couch but I think he’s another money-hungry lawyer interested in Popilla’s dowry.”

I leaned back into the kitchen and indicated that the next set of servers should deliver the lobsters and oysters to the table. I held my breath until the slaves set the snow and shellfish laden platters down and turned back toward the kitchen after an exaggerated bow.

Rúan chuckled as Popilla immediately reached toward the tray to snatch the largest piece of lobster tail on the plate. We watched the diners extract the oysters from their shells with the pointed handles of their spoons.

Snow? I hear you ask. Why yes. If you were wealthy enough, you could afford to have snow carted down from the mountains to grace your table. They even flavored the snow with fruit juice, to make the first flavored ices.

One habit that the ancient Romans had was to share their food with the household gods. When finished with shells or bones from one's food, they would throw it behind them onto the floor. Later, long after the meal had ended and the guests had left, one slave had the task of taking the food away, then burning it on the household shrine. The slave who was chosen to do so was considered to be very unlucky to be the one to remove food from the dead. The habit was so common that the motif of an unswept floor shows itself regularly in ancient Roman mosaics, such as the one below from Hadrian's villa in Tivoli, but now in the Vatican Museum in Rome.

There was often lavish entertainment served up at these meals, ranging from poetry, music, acrobatics, juggling and dancing.

And wine! Of course there was wine. But, not as we drink it today. Instead, it was drank after the meal, and always mixed with water. The Romans also spiced their wine -- it was common to bring your own spice packets to dinner with your particular blend -- and they also clarified wine with nasty ingredients such as lead, charcoal and sea water. They loved wine, however, and there were hundreds of vintages some of them hundreds of years old (and if it became sludge, they would just add more water!). After the meal, the Rex Bibendi, the magister of revels, would mix the wine with the right amount of water. He was also in charge of setting the topics for conversation (often it was the same as is now, no religion or politics!) and making sure that people did not get too drunk. The Romans believed that wearing wreaths made of laurel and other types of flowers would help them stave off drunkenness. And more than one person has conjectured what this wine might have tasted like. Women weren't allowed to drink during the times of the Republic but the rules relaxed as the Roman Empire took hold. The best wine was considered to be Falernian wine and today the grape that is believed to be descended from the grapes that made that ancient wine is that of Falanghina.

From Chapter 12 - Feast of Sorrow

On the drinking couches, the twenty patricians were readying themselves for glass number three. I was sure that Apicius could keep up for at least eight or nine glasses, but I didn’t know how he would manage the last few. We watched as the magister of revels cut the wine with water and the slaves once more went to fill the glasses. At first I worried Livia might try to poison him, but when I saw the wine was directly from the lot of unopened amphorae along the garden wall, I relaxed.

The poet Ovid appeared beside Fannia, leaning over to kiss her cheek in greeting.

“What a delight to see you here!” She beamed.

Aelia held out her hand in greeting and blushed to her toes when he kissed her cheek in welcome.

“Why aren’t you participating?” Fannia asked.

“I’d never make it through the fourth drink!” He tipped his wineglass toward us in a mock toast.

As I suspected, glasses three through five were no problem for Apicius to drink down in one long slow draft, as was required by the rules of the game. Other rules included no burping, no falling off the bench, no declining a drink. None of the participants wanted to be disgraced in front of Caesar. At glass five, one of the city’s more prominent lawyers—and one who had begun drinking long before the party started—fell off his bench. The crowd laughed heartily. Caesar didn’t smile. A wave of his hand brought two burly men over to pick up the drunkard and carry him unceremoniously out of the garden, his worried wife in tow.

Everything went sour after that.

It's possible that the ancient Romans ate out far more often than we do even today. The witty poet Martial once sent this (half-joking) invitation to his guests, suggesting a less luxurious--and possibly less politically fraught--meal than they might get in most patrician households:

Canius, Cerialis, Flaccus--will you come? My dining couch holds seven--there are six of us--add Lupus. The housekeeper from my farm has brought me laxative mallows and the various resources the garden affords amongst which are lettuce which sits close to the ground and leeks for cutting. Burping mint will not be absent nor the aphrodisiac herb. Sliced eggs will crown a dish of Spanish mackerel with rue and there will be a moist belly of tuna from the salting barrel. These are the hors d'oeuvres. This little dinner will consist of a single course: a kid snatched from the mouth of a savage wolf, chops which do not need the carver's knife, the workman's broad beans and unsophisticated shoots. To these will be added a chicken and a ham which has already survived three dinners. When you have had enough I will give you mellow apples, wine which was three years old in Frontinus' second consulship, decanted into a Nomantian flagon. In addition there will be jokes without bile, a freedom not to fear the next morning and nothing you would wish unsaid. My guests talk of chariot racing teams and our cups do not put anyone in court. (Book 10, Epigram 48)

And if you have heard about vomitoriums, fabled rooms adjacent to the dining room where one would go to purge their heavy meal and then go back to eat more...it's just a myth. You can see an actual vomitorium pictured to the left, this one in an amphitheater in Ostia Antica.

About Apicius

The World's First Celebrated Gourmand

Marcus Gavius Apicius was a man who lived in first century Rome, during the time of Augustus and Tiberius. We know a few things about his life, told to us by writers such as Pliny the Elder, Martial, Seneca, Apion and others.

When it comes to food, we know the following about him (shamelessly swiped--for ease of fast explanation/linking--from Wikipedia):

- Apicius dined with Maecenas (70 – 8 BC), Augustus's adviser: Martial, Epigrams 10.73. It is possible that Martial drew this idea from a facile comparison made by Seneca between Maecenas, cultural adviser, and Apicius, gastronomic adviser.

- Drusus (13 BC - 14 September AD 23), son of Tiberius, was persuaded by Apicius not to eat cymae, cabbage tops or cabbage sprouts, because they were a common food: Pliny the Elder, Natural History 19.137.

- The consuls of AD 28, Junius Blaesus and Lucius Antistius Vetus, dined luxuriously at Apicius' house: Aelian, Letters nos 113-114 Domingo-Forasté (Grocock & Grainger 2006, p. 55).

- Tiberius saw a big red mullet in the market and wagered that Apicius or Publius Octavius would buy it. Both men began bidding for it and Octavius won: Seneca, Letters to Lucilius 95.42.

- Apicius lived at Minturnae (Campania). Having heard of the boasted size and sweetness of the shrimps taken near the Libyan coast, Apicius commandeered a boat and crew, but when he arrived, disappointed by the shrimps he was offered by the local fishermen who came alongside in their boats, and comparing them to the excllent crawfish he was accustomed to at his villa, he turned round and returned to Minturnae "without going ashore": Athenaeus, Deipnosophistae 1.7a.

- Apicius was "born to enjoy every extravagant luxury that could be contrived". He advised that red mullet were at their best if, before cooking, they had been drowned in a bath of fish sauce made from red mullet: Pliny, Natural History 9:30.

- Apicius advised that flamingo's tongue was of superb flavour: Pliny, Natural History '10:133

- Based on existing methods of producing goose liver (foie gras), Apicius devised a similar method of producing pork liver. He fed his pigs with dried figs and slaughtered them with an overdose of mulsum (honeyed wine): Pliny, Natural History 8.209.

There are a few more things we know about Apicius, that relate more specifically to his political ambitions so I won't dive deep into that here. And while we know so much about his culinary legacy, there is also so much that we don't know. The grammarian, Apion, apparently wrote a book called "On the Luxury of Apicius," which has since been lost. Several books on sauces bear his name and it is possible that he also owned a cooking school. By the Middle Ages, his name had become synonymous with gluttony and over-abundance. In short, he was filthy rich, and he could afford whatever he wanted. One thing is true, however. He found his niche in the world of food, and for that he still stands out to us, over two thousand years later.

The Apicius Cookbook

Ancient, But Not So Ancient

The best translation of the cookbook we know today as Apicius, is by Sally Grainger and Christopher Grocock in 2006, although you can find an inferior translation online by Joseph Dommers Vehling, published in 1936. The cookbook, often known by it's Latin name, De re coquinaria (On the Subject of Cooking), is a hodge-podge collection of recipes that were compiled into the state by which we now know it, in the fourth century. However, many of the recipes contained within its pages are ancient, dating from the first century or earlier. There are several recipes that have reference to silphium, or laser, which was extinct by 50 A.D. Numerous recipes are attributed directly to Apicius and are thought to have come from his kitchens.

The book is broken up into ten books ranging from meat dishes, vegetables, grains, fowl, dishes of "luxury," quadrapeds, seafood and more. There are a number of recipes devoted to preservation of food, and some for relishes and digestives. There are over 160 recipes for sauces of various kinds within the cookbook. The end of the cookbook also contains a number of recipes by someone named Vindarius, who Grainger believes was a gourmet, and a man of very high status. What remains now as part of the Apicius cookbook was at some point a much larger collection of recipes, and now we only have a few excerpts in the surviving Apicius cookbook.

The recipes were written in Latin, and contain only the barest information for a cook. There are no proportions--it is assumed a cook using the book would know--and the instructions are often somewhat sparse. Some of them aren't really recipes at all:

Apicius 3.17 NETTLES : when the sun is in Aries you may pick stinging nettles against sickness if you like. (tr. by Sally Grainger)

Many of the Apicius recipes are complex, requiring preparations and types of cooking vessels not easily replicated by a modern home cook. As you'll see in the following section, many of the foods are not foods we would eat today.

The earliest version that survives is from the 8th century, but it wasn't until 1498 that the cookbook began to be regularly printed once more.

Sally Grainger recently began a YouTube channel where you can view her recreations of some of the Apicius recipes using a replica ancient Roman oven, pots and utensils! Here's a recipe for a pine kernel (pine nut) sauce:

Make sure you subscribe to her channel to be updated when she has new videos.

The Food of Ancient Rome

Today Ketchup and Parsley are Ubiquitous but 2000 Years Ago It Was Garum and Silphium

Garum

Garum was a condiment that the ancient Romans truly loved. They used it in everything and there were factories on coastlines all over the empire dedicated to making it. Shipwrecks full of amphorae of garum have been discovered in recent years. But what was it?

If you have ever had Thai or Vietnamese food, it's likely you've had something similar to garum. It's a fish sauce, made from the entrails of anchovies, left in the sun to ferment. Sounds delicious, right? Well, the ancient Romans thought so. They put it in everything including their deserts. When I first started trying the ancient Roman recipes, I was worried about the fish sauce, having grown up in an area far from a coast and in a family that ate little fish. But I found that fish sauce gives dishes a salty, umami flavoring when used in small doses. This makes sense as the Romans used salt to preserve their food, but not to salt it--they didn't need to when they had garum.

Today's expert on garum (and really all things surrounding ancient Roman food) is food historian Sally Grainger. She has written extensively on the topic of this ancient sauce. She has a new book coming out in 2021 called The Story of Garum: Fermented Fish Sauce and Salted Fish in the Ancient World.

If you want to make it at home, Boston chef Charles Draghi has a recipe in my companion cookbook to FEAST OF SORROW (check out the link to my cookbook in the recipes section below)

Or if you aren't so adventurous, you can pick up the Italian equivalent, colatura d'alici at Italian specialty shops, or on Amazon. It keeps forever and a little goes a long way.

Silphium

Silphium, also called laser, was an herb that the Romans loved nearly as much as they loved garum. Silphium was an herb cultivated on the island of Cyreanica, off the coast of Libya. The thing is, it was ONLY cultivated there and centuries of ancient Romans and Greeks trying to grow it elsewhere did little good. Eventually they over-farmed it and it went extinct. But even before it became so scarce, it was so prized that inhabitants of Cyrene used to put images of it on coins:

And its fruit, or seed, was heart-shaped, and it's possible that it is where we get the idea of a heart as a symbol for love.

It tasted very similar to another spice that is still common in Middle Eastern cooking today, asafoetida, sometimes called hing or Devil's Dung for its pungent smell. Asafoetida existed in ancient Rome but it was considered inferior in flavor to silphium. What does it taste like? Perhaps the best equivalent would be something like leeks or perhaps garlic.

Silphium was a wonder herb, used medicinally and as a birth control. But it was also a popular herb added to hundreds of dishes in Ancient Rome.

The BBC recently put together a really amazing article on everything Silphium. In it the last sprig of it is described, given as a gift to Emperor Nero as an oddity.

In the cookbook, Apicius, there is a bit of advice on how to make an ounce of silphium last for a year.

Apicius 1.13 (tr. Sally Grainger)

"Put the laser in a spacious glass vessel; immerse about 20 pine kernels. If you need laser flavor, take some nuts, crush them; they will impart to your dish an admirable flavor. Replace the used nuts with a like number of fresh ones."

BUT....have they found Silphium? Some researchers believe they have, in a remote part of Turkey.

And of course, food archaeologists such as Sally Grainger and Farrell Monaco were excited to taste it.

The Exotic (or at least to us today)

These foods would not have been found on the table of the average Roman. They were often costly or difficult to acquire, and subsequently prepare.

FLAMINGO: Pliny the Elder told us that Apicius loved flamingo tongue, but we know from the cookbook that wealthy ancient Romans loved flamingo in general. And yes, flamingos can be found in Italy.

PEACOCK: Throughout the centuries peacock has been found on the tables of the very rich. There are a variety of ways that the ancient Romans prepared the bird, and Apicius tells us that when it comes to meatballs (or in the UK you may see the terms forcemeat or faggots), peacock ranks first, then pheasant, then rabbit, then chicken and tender young pork meatballs rank fifth.

CRANE, PARROT and other birds we don't find commonly eaten in modern times were relished back in the day.

SONGBIRDS: little birds, such as figpeckers, sparrows, thrushes and ortolans were often defeathered, then cooked whole, to be eaten, bones and all. It was a tradition that the French continued until 1999 when ortolan populations fell dangerously low and the hunting and killing of the bird was banned.

DORMICE: The edible dormouse was much beloved by the Romans, so much so that they brought the delicacy with them when they conquered Britain. They raised these tree-dwelling mice in big jars called glirarium, designed specifically to fatten them up. They were stuffed and fried and eaten up, bones and all. In parts of Croatia and Slovenia they are still eaten.

ALL THE PARTS: Womb, tripe, udders, brains, testicles, kidneys...all of it could be found on the plates of the ancient Romans. Sow's vulva was a particular delicacy. While some sources suggest that eating the womb after a birth was desirable, Joseph Vehling in his translation of Apicius tells us:

The vulva of a sow was a favorite dish with the ancients, considered a great delicacy. Sows were slaughtered before they had a litter, or were spayed for the purpose of obtaining the sterile womb.

ELECTRIC RAY: There are two recipes in Apicius for ray, one of which contains pepper, lovage, parsely, mint, oregano, yolk of egg, honey, garum, sweet wine, mustard, vinegar and if you like, raisins.

BULBS: Today we eat bulbs all the time (onion, garlic and leeks), but in past centuries,many other types of flower bulbshave commonly been eaten. Apicius includes four recipes for flower bulbs. The bulbs are usually fried in oil and served in a sauce. You can still find this dish in many remote parts of Italy today. My husband's uncle remembers eating them here in the US as a child of Italian immigrants from Puglia.

FIG FATTENED LIVER: Foie gras was nothing new to the ancient Romans, having likely acquired the taste from Greeks who learned it from the Egyptians. But Apicius took it to another level, fattening up his pigs with dried figs, then giving them wine, which would reconstitute those figs and kill the pigs, supposedly leaving their liver full of flavor. And yes, there was a sauce for that.

MILK FED SNAILS: The ancient Romans kept their snails in special enclosures called choclearium. They would fatten the snails on a mixture of wine and flour, or as described in Apicius, on milk. The snails they used are called Roman snails, or sometimes Burgandy snails. They are often kept as pets.

MILK FED SNAILS: The ancient Romans kept their snails in special enclosures called choclearium. They would fatten the snails on a mixture of wine and flour, or as described in Apicius, on milk. The snails they used are called Roman snails, or sometimes Burgandy snails. They are often kept as pets.

POSCA: Posca was a red-wine vinegar concoction that Roman soldiers drank. It was made by mixing sour wine or vinegar with water and, like all wine of the day, mixed with herbs for flavor. The Romans believed it helped fortify the soldiers and indeed, it did help prevent scurvy and provide some anti-bacterial protection.

The More Familiar

- Tapenade - this caper and olive spread was as popular in ancient Rome as it is today. While Apicius does not include a recipe, you can find one in Columella's, De re Rustica and Cato the Elder's book On Agriculture.

- Foie gras - I mentioned foie gras previously, but beyond the fig-fattened pigs, the ancients used to fatten up all manner of small birds to snack on their livers. Don't let a Frenchman tell you different (but yes, they did perfect the method).

- Fried dough - Living in the city meant that you were often on the go. And just like today, dough fried in oil was popular. See the recipe section for an ancient Roman fritter that you can make at home today.

FROM CHAPTER 19 - FEAST OF SORROW

The wedding prandium was an all-morning affair. The guests retired to couches in the atrium to eat the most elaborate breakfast I had ever devised. I couldn’t bear to sit with the crowd and instead helped Timon deliver course after course of dormice in honey, more spiced fritters, platter upon platter of fried anchovies, flatbreads with goat cheese and pepper, medallions of wild boar and individual bowls of hazelnut custard. Each dish was served on golden trays. The guests were given gold spoons and napkins dyed in Tyrrhenian purple—lavish gifts they could take home. In between each course, barely clad serving girls showered the guests with rose petals and helped them wash their hands.

- Haggis - While it's the national dish of Scotland today, it was the ancient Greeks and Romans who first started stuffing meats and spices into a cow or pig's stomach or lung, then tie it up and boil it. Apicius includes a recipe for boiled stomach, stuffed with brains, eggs, pine nuts, peppercorns, ginger, anise, pepper, lovage, silphium, rue, garum and oil.

- Meatballs - While there wasn't spaghetti to accompany ancient Roman meatballs, that didn't make them any less popular, especially as a street food. There are a number of recipes in Apicius for meatballs, which were always served in a sauce.

- Absinthe/Vermouth - No, it wasn't likely anything similar to the liquors we know today, but as the wormwood recipe in Apicius shows us, it's where they get their start.

- French toast - yes, that's right. This popular breakfast dish originated in ancient Rome.

Apicius 7.11.3 Another Sweet Recipe (tr. Sally Grainger)

Take the crust off a white loaf and break it into quite large pieces. Soak in milk, fry in oil, pour on honey and serve.

- Fritattas, omelettes and quiche - The Romans were quite fond of eggs and there is an entire chapter in Apicius dedicated to patinae, dishes made with eggs. You can find omelettes made with roast pine nuts, honey, pepper, garum, milk, eggs and oil, to extremely complex dishes such as the Apician patina which includes cooked udder, flaked fish, chicken meat, figpeckers or cooked breast of thrush and "whatever finest quality things there may be."

- Flatbread - A staple of ancient Roman life, flatbread is truly one of the most ancient foods that we still eat today. There are hundreds, if not thousands, of different types of flatbreads from cultures around the world.

Ancient Roman Recipes

Taste the Flavors of Ancient Rome

One of the greatest joys of writing a book about Apicius was having the opportunity to try out the myriad of recipes. It was sometimes a challenge to make them palatable for the modern audience, especially with fish sauce as an ingredient in nearly everything. One of the things that I loved most about the process was being able to make the connection to certain types of foods and Italian dishes, to be able to recognize something modern but that clearly had its roots in the very ancient. I find this is true especially when I'm in Italy and I hear about a dish or see one on a menu that is really not that different than something the ancients would have eaten.

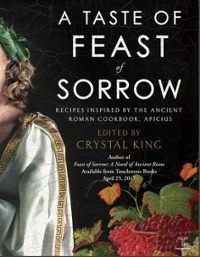

To celebrate the publication of FEAST OF SORROW, I worked with several chefs, cookbook authors, and food historians to put together a collection of 23 recipes for the home cook, inspired by Apicius. You can check it out for free here:

But don't stop there, here are a few more recipes to whet your appetite for all things ancient Roman:

- Parthian Chicken

- Honey cake (interpreted by Crystal King)

- Sauce for Mushrooms

- Glykinai – Sweet Wine Cakes (Ancient Roman Crackers)

- Mustard Beets (Ancient Rome)

- Palathai – Easy, Quick and Delicious Roman Fig Cakes

- Tiropatina, a sweet custard and Libum, ancient cheesecake (from food historian Farrell Monaco at Tavola Mediterranea, a gorgeous site with many recipes from Apicius and others)

- Patina de Rosas, brains and roses (from Andrew Colletti at Pass the Flamingo, a site with a number of fascinating ancient recipes)

- Broad Beans à la Vitellius (from Coquinaria, an excellent site with many recipes)

- Mustacei or must rolls from Cato, De Agricultura (from Following Hadrian)

- Fennel Roasted Pork Loin (and a few other inspired recipes, from Quench)

- Milk Fed Snails (from Romans in Britain)

- Ancient Roman Bread (from ZMEScience)

- Mustacei or must rolls from Cato, De Agricultura (from Following Hadrian)

- Olive Dip – Epityrum (from Ancient Recipes)

- Savillum, an ancient pastry (from Z Tasty Life)

- Stuffed Kidneys (from the BBC)

- Lucanian Sausages (and a few other recipes, from PBS)

- Roast Venison (from Honest Food)

- Roman cheese (from KCET)

- Ancient Roman Mustard (from Hunter, Angler, Gardener, Cook)

- Ostrich Ragut, Roast Wild Boar (and other recipes, from University of Chicago Press's site)

- Numidian Chicken (from Pass the Garum, a site with a bevy of ancient recipes)

Pliny the Elder's Chickling Vetch Sourdough Bread Starter

by Farrell Monaco

Honey Fritters

by EmmyMade in Japan

Ancient Roman Mussels

from Tasting History

Books and Resources

Non-Fiction and Fiction about Ancient Rome

Want to continue your historical adventure to the world of the past? Here are some of my favorite resources on food and the world of first century Rome.

Non-Fiction

- Apicius, translated by Sally Grainger and Christopher Grocock

- Cooking Apicius by Sally Grainger

- Empire of Pleasures, by Andrew Dalby

- The Philosopher's Kitchen: Recipes from Ancient Greece and Rome for the Modern Cook by Francine Segan

- A Day in the Life of Ancient Rome: Daily Life, Mysteries, and Curiosities by Alberto Angelo

- A Taste of Ancient Rome by Ilaria Gozzini Giacosa

- Roman Cookery: Ancient Recipes for Modern Kitchens by Mark Grant

- Around the Roman Table: Food and Feasting in Ancient Rome by Patrick Faas

- The Classical Cookbook by Andrew Dalby

- SPQR by Mary Beard

- The Twelve Caesars by Seutonius

- Augustus by John Williams

- Ancient Rome: The Rise and Fall of an Empire by Simon Baker

- Natural History: A Selection by Pliny the Elder

- A Handbook to Life in Ancient Rome by Lesley and Roy A Adkins

Fiction

- Metamorphoses by Ovid

- The Satyricon by Petronius

- The Aenid by Virgil

- The Confessions of Young Nero and The Splendor Before the Dark by Margaret George

- I, Claudius by Robert Graves

- The Mistress of Rome series by Kate Quinn

- Palatine, Galba's Men, Otho's Regret, Vitellus' Feast by L.J. Trafford

- The Uncertain Hour by Jesse Browner

- I Am Livia and Daughters of the Palatine Hill by Phyllis T. Smith

- A Tale of Ancient Rome series by Elisabeth Storrs

- From Unseen Fire by Cass Morris

- Roma by Steven Saylor

- Imperium and Pompeii by Robert Harris

- The Course of Honor by Lindsey Davis

BUY FEAST OF SORROW NOW

Set amongst the scandal, wealth, and upstairs-downstairs politics of a Roman family, Crystal King’s seminal debut features the man who inspired the world’s oldest cookbook and the ambition that led to his destruction.

On a blistering day in the twenty-sixth year of Augustus Caesar’s reign, a young chef, Thrasius, is acquired for the exorbitant price of twenty thousand denarii. His purchaser is the infamous gourmet Marcus Gavius Apicius, wealthy beyond measure, obsessed with a taste for fine meals from exotic places, and a singular ambition: to serve as culinary advisor to Caesar, an honor that will cement his legacy as Rome's leading epicure.

"If true gastronomy resides at the intersection of food, art and culture, then Crystal King's debut novel can only be described as a gastronomical delight . . . satisfying, but readers are left hungry for more." ~Associated Press

A CHRONOLOGY OF ITALIAN HISTORY AND ADVENTURE

Crystal King’s fiction offers a passport through time, through stories of history, cuisine, and mythology that span two thousand years of the Italian experience.

The journey begins in the 1st Century AD with Feast of Sorrow, immersing readers in the opulent and treacherous kitchens of ancient Rome alongside the legendary gourmand Apicius.

The narrative thread pulls forward to the Renaissance in The Chef’s Secret, revealing the delicious and mysterious life of Bartolomeo Scappi, the private chef to several Popes and cardinals.

Moving into the modern era, In the Garden of Monsters explores a retelling of Hades and Persephone, set in 1948, where the lines between art and madness blur in the shadow of a garden of stone monsters in Bomarzo Italy.

Finally, the timeline arrives in 2019 with The Happiness Collector, bringing the ancient influence of the gods into a contemporary world.

While the eras change, the muse remains the same: the enduring, sun-drenched mystery of Italy.