Everything you ever wanted to know about:

Italian Renaissance Food

by Crystal King, Author of The Chef's Secret

Introduction

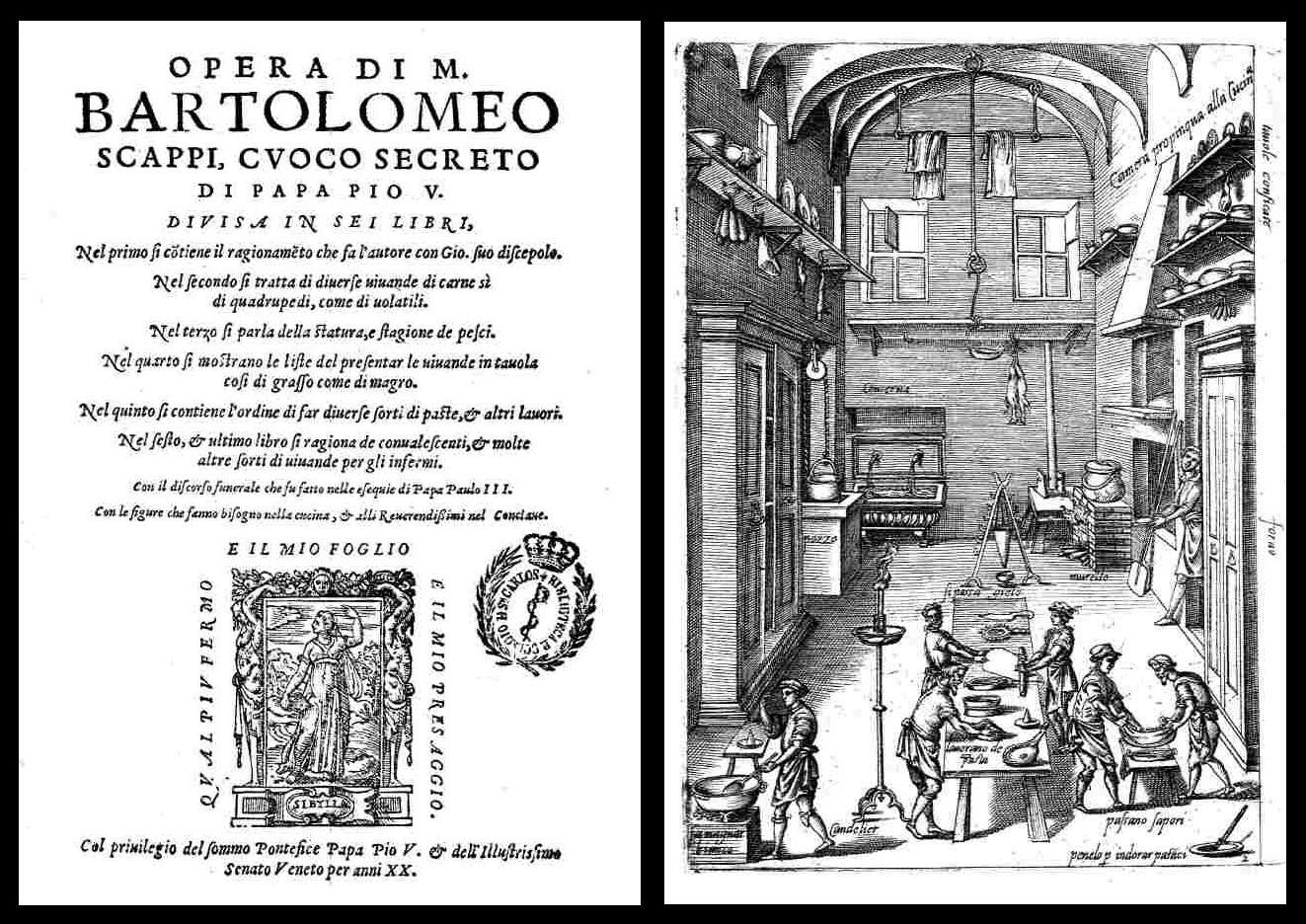

When I was researching my first novel, FEAST OF SORROW, I kept coming across a cookbook that was mentioned in a number of Italian culinary compendiums—L'Opera of Bartolomeo Scappi, or the "works" of Bartolomeo Scappi. It's a cookbook that was published in 1570, contains over 1,000 recipes, and was a bestselling cookbook for almost 200 years after its publication. Of course, I had to get this cookbook! I wasn't disappointed. Besides the amazing food, within the pages I discovered the voice of Scappi, a man we know very little about, but the flavors and recipes are truly unforgettable—and many of them have stood the test of time, over 500 years. I fell in love with this long gone person, and wanted to bring him to life for modern audiences, and share some of my knowledge about Italian Renaissance food, which is why I wrote THE CHEF'S SECRET.

The Beginnings of Modern Italian Cuisine

When you think of the Renaissance I'm guessing images of Michelangelo sculptures, or the sumptuous gowns worn by the likes of Lucrezia Borgia are more likely to come to mind than what foods might have been served during that era. In fact, the Renaissance is when the types of Italian food we know and love today start to become more familiar, with shaped and filled pastas, pies and pastries, and even desserts such as zabaglione. On this page, I'll take you on a mini culinary tour of everything Italian Renaissance food.

Food in Renaissance Culture

The shift between the Middle Ages and the Renaissance

As Italy came into the Renaissance period, everything about dining became more refined. Lords no longer dined with their vassals, but instead developed noble courts. Table manners came into play. Global trade routes were more firmly established and new foods were introduced from the New World. Sugar was introduced and spices were more prized than ever.

The late medieval period and early Renaissance was also deeply focused on the idea of balancing food against the individual temperament,hearkening back to the writings of the ancient physicians, Galen and Hippocrates. The humoral diet was exceedingly complex, however, and by the middle and end of the Renaissance this had fallen by the wayside. Abiding by this diet was particularly prohibitive for nobility looking to show off their wealth through food and banquets. But, "its vestiges still linger today in such popular lore as “feed a cold, starve a fever” and in descriptions of taste sensations, from hot peppers to dry martinis."

By the latter part of the Renaissnce, tastes had begun to shift from the cloying spices and acidic flavors of the Middle Ages (think sauces similar to the salad dressings of today, made with wine, bitter grape juice, or vinegar). In the Renaissance, a new richness appeared and sugar became prevalent in most dishes--and counter to what we know today, because it was naturally sweet, it was considered "healthy" so the chefs of the time used it in everything. Butter and oil also became popular to thicken sauces.

And, the advent of the printing press led to the quick development of cookbooks, which in turn, started to help spread the ideas of noble chefs across Europe.

At the Heart of Italian Life

A tavola non si invecchia. is an Italian proverb that means, "At the table with good friends and family you do not become old."

Just as today, food was the cultural center of life across Renaissance Italy. Food marked religious holidays. It was central in wedding ceremonies. After a baby was born, friends and family brought the new mother food that was nourishing and sweet. And food played a role at funerals, including at Easter when a big feast was held to celebrate the Resurrection. Food was also medicine and the cook played a role alongside the doctor in medieval and Renaissance life.

A wide variety of food was also available in most cities and towns. There were numerous markets and vendors that hawked all manner of meats, fish, vegetables, breads and pastries. It was common to see venditore on foot, such as this ciambelle seller, who carried the crunchy but soft rounds of bread (they were a precursor to the bagel of today) on sticks in his basket.

.jpg?width=445&name=Venditore%20di%20ciambelle%20(1).jpg)

The Rich and the Poor

Food was a major differentiator between the nobility and the peasant classes. but both depended on two things: bread and wine. Bread was the main source of calories for the poor, but it was enjoyed by the wealthy as well. By this time in history, white bread was common, but the whiter the bread, the more expensive it was. If it was a bread made from mixed grains, it was only suitable for the poorest of Italians. There were charitable organizations who helped make sure the poor were fed, and much of that food was bread. The wealthy could afford elaborate pastries, pies and fritters.

Wine was also a common denominator, Grape vines were easy to grow all over the country, and even peasants could make their own wine. Some common grapes of that era include prosecco, lambrusco, sangiovese, malvasia, nebbiolo, albano and chianti. Wine was always diluted with water or ice, and could often be flavored with spices, honey or licorice. It was drank by children and adults alike because the water was often suspect, and they drank much higher quantities of alcohol than we generally do today. But, as it is still the case in Italy, being drunk, especially in public, was frowned upon.

The 1500s were also a time of a number of treatise about health, and many of them remarked upon how the rich and the poor should eat, as though their physiology was different. The World of Renaissance Italy encyclopedia tells us about Dr. Baldassare Pisanelli of Bologna, who wrote in 1585 that "the rich man's proper diet will sicken the poor man just as quickly as the poor man's diet will cripple the noble. When peasants dine on birds, they get sick." He was espousing information that was commonly believed at the time, that the closer to the ground the food is, the more it is a food for peasants, while food that is higher, such as fruit from trees, long legged-animals, and of course, birds, were better suited for the nobility. This is also why the cookbooks of the time don't contain many vegetables, and if they do, they are taller foods, with leafy greens, as they were preferable to root vegetables that were underground. If you were to use a lowly food at a Lord's table, it should be ennobled by a food of a higher order. In other words, garlic with fowl would be acceptable.

In general, the poor ate more of foods low to the ground, such as turnips, garlic, onions and carrots, while nobility dined on "higher" foods such as artichokes, peaches, pheasant, and pears.

Mealtimes and Dining Details

In medieval times, two meals a day was most common, around noon, and just before dusk. As the types of meals served became more elaborate, the times were often pushed out to accommodate the additional preparation and dining times. That led to people breaking their long fast, by having a small snack upon waking, usually a little bit of bread, and perhaps some butter or cheese.

By the Renaissance, the mid-day and evening meals could be quite elaborate in noble households, and for grand occasions, the banquet also provided dancing and entertainment which might often be followed by additional drinks and desserts.

At a banquet, the guests would be provided with water (often scented with rosewater) and a towel to wash their hands before the meal began. It was common for many courses to be served at each meal, often up to ten or twelve courses. Tables would be layered with tablecloths which would be removed at each course to provide a clean slate for the next set of dishes. The courses could sometimes include as many as 100 dishes each, which meant that a very fancy feast for the Pope or an Italian prince may have as many as 1,000 dishes served throughout the meal! But not everyone would be served each dish—the most luxurious dishes (e.g. pheasant gilded with gold, or perhaps a rare meat, such as turkey) would be reserved for the most important people at the table.

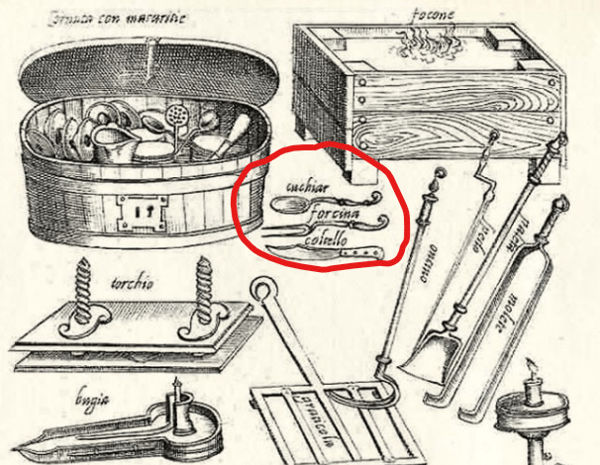

The setting of the table was not that dissimilar to what we know today. Each diner would have a spoon and a knife, but it wasn't until toward the end of the 1500's, that the fork became commonplace at the Italian table.

The Fork

We know that forks were available in the world of ancient Egypt, Greece and Rome, but were likely used to hold meat when carving, or lifting meats from pots or the fire. Forks started to appear in 7th century Byzantium, but it wasn't until 1004 when the son of the Venetian Doge was married to Princess Maria Argyropoulaina, the Greek niece of Byzantine Emperor Basil II. She brought with her from Byzantium a set of golden forks. But the Venetians were not taken with the practice and she was roundly denounced, and one clergyman said, "God in his wisdom has provided man with natural forks—his fingers. Therefore it is an insult to him to substitute artificial metal forks for them when eating.” And two years later, when she died of plague, a theologian, Peter Damian, condemned her further. “Nor did she deign to touch her food with her fingers, but would command her eunuchs to cut it up into small pieces, which she would impale on a certain golden instrument with two prongs and thus carry to her mouth. . . . this woman’s vanity was hateful to Almighty God; and so, unmistakably, did He take his revenge. For He raised over her the sword of His divine justice, so that her whole body did putrefy and all her limbs began to wither.”

The fork gained its five tines in the 1100s. It wasn't until the late medieval period that forks began to show up on noble tables, and in 1570, Bartolomeo Scappi shows us the first fork ever depicted in print, appearing together with spoon and knife.

Interestingly enough, nobility in the Renaissance also carried toothpicks with them. They could be elaborately made from gold or silver, in the shapes of scimitars, cupids or mermaids, and were often threaded with a chain to hang about the neck or from a girdle.

Eating Out

Just as we do today, the people of Renaissance Italy often met over meals, or ate at a restaurant when they were traveling. While most denizens of a city took most of their meals at home with friends and family, there were a variety of options for individuals looking for a public place to eat.

The markets themselves were full of vendors that could provide a quick snack to eat on the go. But there were also osterie, (inns) or fraschette, wine shops. Travelers stopped in them when they were spending time in the city but locals could also partake in simple fare and local wines. In many cases families could come for a meal, and the osteria would serve the wine.

One of the oldest pubs in the world is Osteria del Sole which got its start in 1465 in Bologna. It still exists today and functions much like it did five hundred years ago. You bring the food, and they'll pour the wine. If you can read Italian, you'll see that one of the signs on the front says Chi non beve: È pregato di stare fuori, which means, "If you don't drink, please stay outside." If you visit Bologna, check out one of the nearby food stalls and head to this little osteria to step backwards in time and dine just like they have for hundreds of years. This pub shows up in my current novel-in-progress!

Feasting in the Renaissance

Dining in wealthy Renaissance households started with the place in which the table was set up. In the late 1400s the designation of a specific room in which to dine began to take shape, Many villas had elaborate dining rooms (or sala) with beautiful painted ceilings and easy access for the servers to appear with food from the kitchen. Wealthy nobles began to incorporate outdoor dining locations into their villas. Banker Agostino Chigi developed his beautiful villa (now called The Farnesina, in the Trastevere, Rome) with a loggia that could open up into the gardens.

Agostino had the painter, Raphael, decorate the ceiling with beautiful frescoes to give his guests something to delight in as they dined. Further down in the garden, he also had a beautiful dining area built on top of a natural grotto. When he entertained Pope Leo X, he grandly threw all his gold and silver plate into the Tiber river after the meal to show them that wealth didn't matter to him. Afterward, he had his servants pull up the nets from beneath the water to retrieve it all.

At Villa d'Este in Tivoli, a number of houses, casinos and little grottoes where diners could enjoy a meal were incorporated into the massive fountain-laden (over 500 of them!) grounds. One terrace even has a water organ that would play music at intervals for guests (and you can still see it play if you visit). At Villa Lante you can see a table inspired by Pliny who said he had floating dinner plates at his villa in Tuscany.

Inside, each room would have a credenza, or sideboard where the cold foods for the table were kept to be served throughout a meal. The credenza also held elaborate plates that helped to demonstrate the wealth of the palazzo's owner. The credenza became so important that you'll often see it depicted in paintings, or painted on the walls of a palazzo such as in the one below.

Fresco by Giulio Romano, Palazzo del Te, Mantua c. 1524-1535

FROM CHAPTER 21 - THE CHEF'S SECRET

“We will outdo all the other anniversary feasts, my boy. Even the decadent Leo X will smile down upon us from the heavens when he sees what I have planned.” Bartolomeo clapped Giovanni on the shoulder. He was pleased by the progress his apprentice had made over the last two years. Little did Giovanni know that the grandeur of the feast to celebrate the anniversary of the coronation of Pius V was less about the Pope and more about Bartolomeo wanting to show his son what marvels could be done through mastery of the kitchen.

“How many platters did you say we are serving?” Giovanni asked.

Bartolomeo glanced at the parchment in front of him. “One thousand, one hundred and sixty-seven.”

Giovanni peered at the paper. “Fifty dozen pieces of light white bread? A thousand cockles with orange peel? Pastry castles with live birds? And a gelatin with the Pope’s face? Mi dispiace, Uncle, but is making this much food even possible?”

Bartolomeo waved a hand as though the quantities were nothing. “Bah, the feast I did for Emperor Charles was far more elaborate. You have never imagined how many sugar sculptures we did for that luncheon!”

“So, I’ve heard.” Giovanni did not seem convinced.

“Worry not, Gio. We have one hundred fifty men between the Vaticano kitchen and the Pope’s private kitchen, and I am asking the Roman Cardinali to send men from their palazzi as well.”

Giovanni ran his hand through his dark locks, a nervous habit Bartolomeo knew well. “And we do this every year? Dio mio. I’m never going to remember all this,” the young man fretted. “How do you keep these details straight?”

“Someday you’ll feel comfortablcg even bigger feasts.” Bartolomeo remembered how nervous he had been the first time he had to execute a large banquet for Cardinale Campeggio. Now it all seemed a simple feat, but back then he had bitten his nails to the quick with worry.

“Where do we start?”

“You oversee the pasta,” Bartolomeo told his apprentice. “We can make much of it in December and hang it to dry. I also want you to arrange for the snails and for all the fowl deliveries, which we should start on right away. Most of the birds should be delivered live unless they come in the day or two before, but I do not recommend that—it’s too unpredictable. Have them delivered to the Vaticano farm and we can slaughter them when we are ready.”

Giovanni took the paper and scanned it. “What of molds for the sugar sculptures and the gelatins? Don’t those take time to have carved?”

Bartolomeo smiled. “Worry about the pasta, snails and the fowl. I’ll worry about the rest.”

“Sì, sì.” Giovanni shuffled off, his eyes still on the paper. Bartolomeo smiled after him. It was a lot for someone so young to manage—he was barely twenty—but Bartolomeo had faith in his apprentice. Giovanni perched himself on a stool at his regular table in the kitchen. He began scratching notes on another piece of parchment as he scanned the list he had just been handed. He was so proud of his son, the son who would only know of him as an uncle. The thought of it pricked at the edge of his heart, but he pushed away the idea, turning back to the task at hand, determining how much flour a dozen four-feet high pastry castles might require.

Yes, there really were 1,167 dishes planned for the anniversary luncheon to celebrate the first full year of Pope Pius V's reign. Bartolomeo Scappi includes a number of menus in his cookbook, and many of them have hundreds of dishes served, often to just barely a dozen people. In fact, all the descriptions of food in the passage above were taken from the menus in Scappi's cookbook.

Feasts would often have as many as ten courses served, with a wide variety of sweet and savory dishes served at each one. The idea of holding the sweet dishes till "dessert" had not yet come into favor and it was not uncommon to see a sweet pastry on the table alongside a boiled rabbit dish.

One thing that would have been at all of Bartolomeo's banquets were sugar sculptures. These beautiful (and inedible) sculptures were all the rage in the Renaissance as sugar became more and more available from the New World. In the Renaissance sugar was a costly luxury and to sculpt elaborate designs from it was one of the ultimate demonstrations of wealth and power in this time.

The sculpture here of the lion and the bull was featured at the 2015 exhibition at Palazzo Pitti recreating one of the most amazing wedding feasts, depicting the proxy marriage of Maria de’ Medici and Henry IV of France in 1600. To see more about this recreation feast, see the video below the information about napkin folding.

The sculptures could be quite elaborate and many sculptors of the day tried their hands at making sculptures or molds, including Leonardo da Vinci and Titian.

The love of sugar sculptures spread throughout Europe. There are many accounts of tablescapes meant to awe the diner, such as this one from the wedding feast of Johann Wilhelm in 1585.

In his cookbook, Bartolmeo Scappi describes many sugar and butter sculptures. One menu lists “one elephant with a castle on its back (which you can also see in the image above!),” “Hercules slashing at the mouth of a lion,” “a camel with a dark king above,” and “a unicorn with its horn in the mouth of a serpent.”

White sugar wasn't easily available until the 17th century, and through most of the Renaissance these sculptures would have been made with some form of brown sugar and then colored with vibrant vegetable dyes.

Sculptures were usually made with a paste of sugar, water and gum arabic. "Sugar paste used in the Renaissance period is comparable to wedding cake fondant we see today. When it hardens, this sugar paste has the color and substance of Necco Wafers."

Interested in making your own sugar sculptures? Here's YouTube to the rescue:

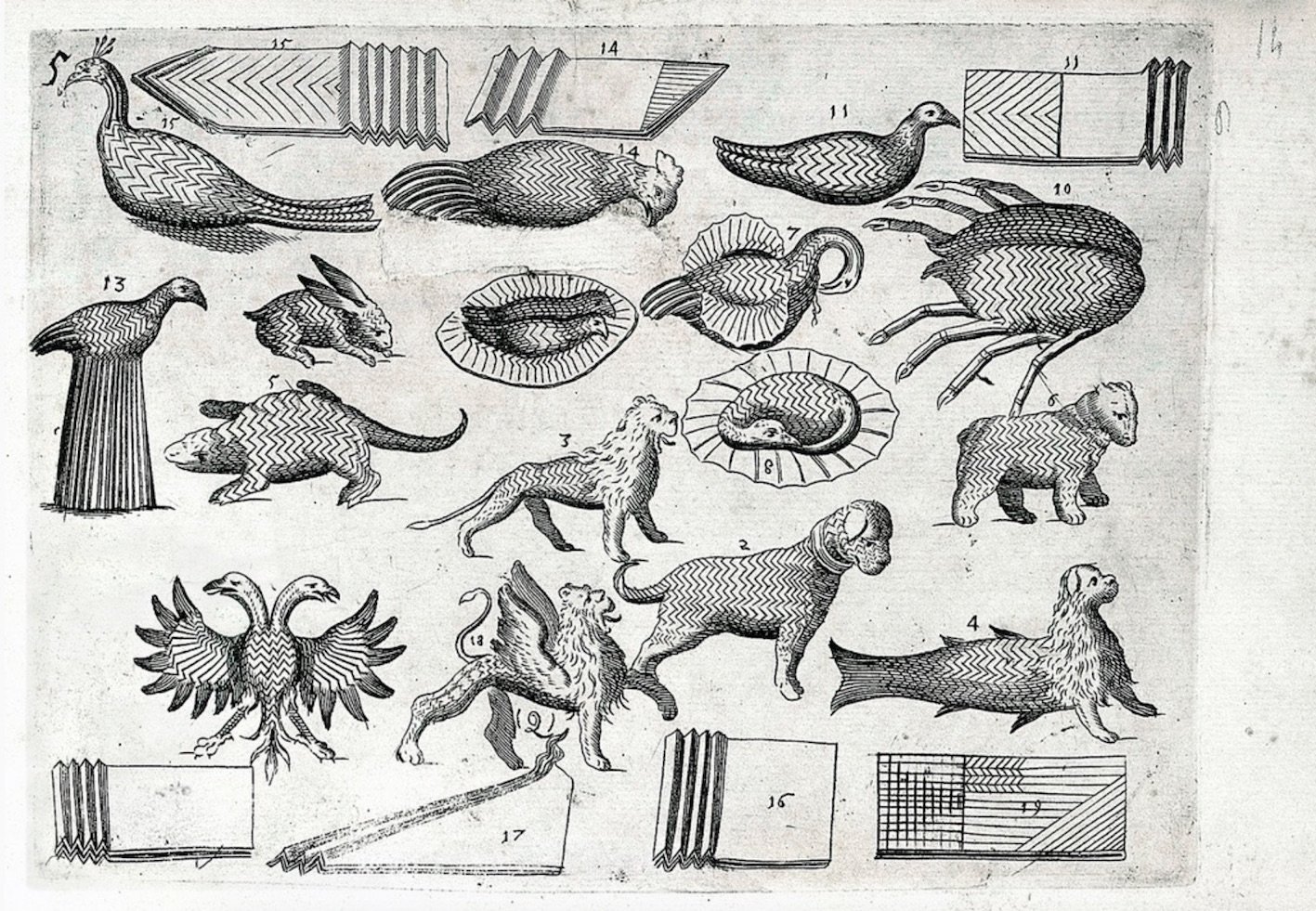

Eventually the art of napkin folding took the place of some sugar sculpture displays. Mattia Giegher's 1629 book of the art of the trinciante (meat carver), The Three Traits shows some ways that napkins might be folded into elaborate shapes.

His entire book is online here and it's full of amazing illustrations of a luxurious bygone era. Check out the video of the 2015 Palazzo Pitti exhibit that demonstrates some of these incredible creatures as well as some beautiful sugar sculptures:

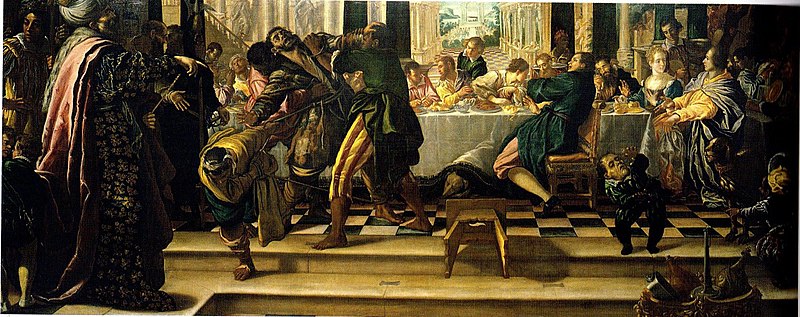

Banquets could last for many hours and entertainment was needed to keep the guests occupied. Most noble courts employed (or owned) a court dwarf or two. They were often given to other households as gifts or traded among families. Even the popes had a court dwarf. These dwarves were both considered natural buffoons based upon their looks, but were also often used as court jesters and were an important part of the entertainment of a feast.

La cacciata dell'invitato indegno (The expulsion of the unworthy guest) by Fra Semplice da Verona (1589 – 1654)

One such dwarf, Dottor Boccia, was court jester to Julius III, Marcellus II and Paul IV. When Pius IV came into power, one of his very first acts was to expunge the dwarf. However, many dwarves became close with the families in which they were kept, and sometimes became diplomats for the rulers they served. When they reached the end of the time in court, they were often given gifts and pensions.

In addition to buffoons and jesters, banquets would have musical accompaniments, plays performed between courses, acrobats, belly dancers, and sometimes (outdoors) even fireworks.

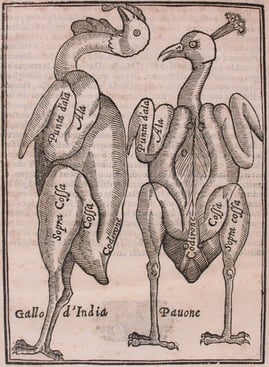

The delivery of the food itself was part of the entertainment. The trinciante was front and center at a banquet. The role of a meat carver was a special one, not beholden to the steward or the maestro of the kitchen. He was a master swordsman, held his own titles and lands, and having one serve you was a great honor. Vincenzo Cervio was one of the most famous, and his book Il Trinciante, describes all manner of carving meats in aria—in the air—with the meat falling perfectly onto the plate of the noble he served. A big feast would have multiple trincianti.

In this image you can see an illustration from his book, which features a peacock (pavone), and the gallo d'India (chicken of India), the turkey, which was a highly sought-after meat from the new world.

In his book, Cervio also describes a table brought out from the kitchen with the meat he was to carve. The table was on wheels and pulled by two jaguars!

There was also more than one occasion where birds might fly from a pie. Scappi describes a banquet with live birds flying out of pastry castles! And you thought that four and twenty blackbirds was just a nursery rhyme.

Renaissance Food Influencers

A quick note...some of the text in this section is taken directly from Wikipedia for expediency and for the sake of aggregation. Clicking through on their names will take you to the full page.

Before Bartolomeo Scappi came out with his famous cookbook, there were a few others who helped pave the way for him:

Maestro Martino de' Rossi, made his career in Italy and worked as the chef at the Roman palazzo of the papal chamberlain ("camerlengo"), the Patriarch of Aquileia. Martino was applauded by his peers, earning him the epitaph of the prince of cooks. His book Libro de Arte Coquinaria (The Art of Cooking) (c. 1465) is considered a landmark in Italian gastronomic literature and a historical record of the transition from medieval to renaissance cuisine. It's divided into 6 chapters: meat, side dishes, sauces, pies/tarts, fried food and egg dishes, fish. These recipes were common and most had been previously published in other pamphlets and books of the time.

Bartolomeo Sacchi known as Platina, who was a major player in Italian humanism, considered Martino as the best chef of his time. Platina even used nearly half of Martino’s book as the technical base of this treatise, Opera On Right Pleasure and Good Health., published for the first time in Rome in 1474 in Latin. It was the first printed cookbook to circulate throughout Italy. It was later published in Venice in 1487 in Italian and then spread across Europe, having been translated into French, German and English.

Cristoforo Messibugo - From 1524 to 1548, di Messisbugo served as a Master of Ceremonies at the courts of Alfonso I and his son, Ercole II d’Este, in Ferrara, where he organized many lavish banquets.

Jen Smith from MedMeanderings tells us: "Table manners at the end of the Middle Ages were appalling. Everyone ate out of the same pot. Meals were served in one large chunk, from which everyone present cut a piece for themselves. Poultry was not carved up before being put on the table. and people pulled even birds as big as pheasants apart with their hands." Messibugo changed that, introducing the idea of carving as part of courtly manners. He was known to carve roasts and other foods so expertly that he never touched them with his fingers, but only with knives and forks that had been provided for that purpose.

His cookbook Banchetti, composizioni di vivande e apparecchio generale or Banquets, Arrangements for Food and Drink, and Organisation in General, which was published posthumously in 1549, is addressed to those preparing princely feasts and provides detailed descriptions of the menus for his official banquets at the Este court.Beluga sturgeon abounded in the Po River in the 16th century and they were a frequent capture. The first known reference to the preparation of sturgeon caviar in Italy is in Messisbugo's books. He described how to prepare the caviar both to be consumed fresh and to be preserved.

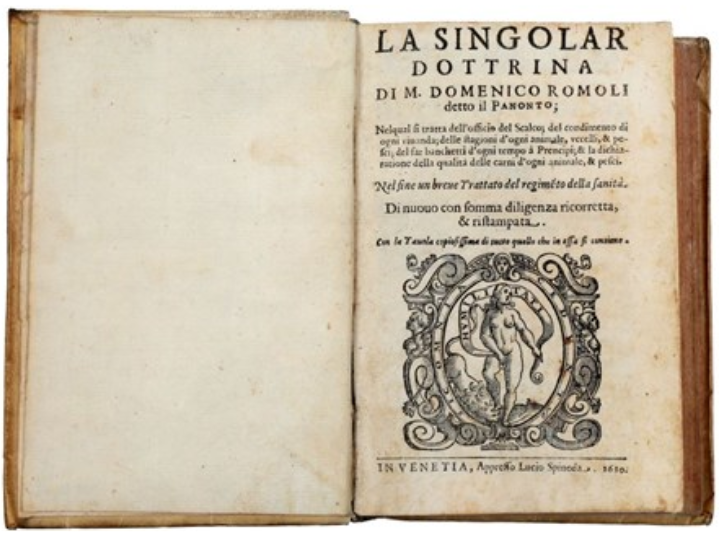

Domenico Romoli is a bit dear to my heart, having decided he would make a great villain for THE CHEF'S SECRET. In real life, he didn't do any of the things I had him do in my novel. Instead, he wrote La singolar dottrina (The Singular Doctrine). He had a fun nickname that people called him, Panunto, which was the name of an oily bread recipe he was known for, and he gave the cookbook the same name as well. The book was published in Venice in 1560 and reprinted in a few editions in the 16th century and the first half of the 17th. The work did not present any major innovations in recipe writing, but its merit lies in its organization of complex service elements and its definition of assignments, relationships and hierarchy. His book is also interesting in that he highlights the seasonality of ingredients by including a recipe for each day of the year.

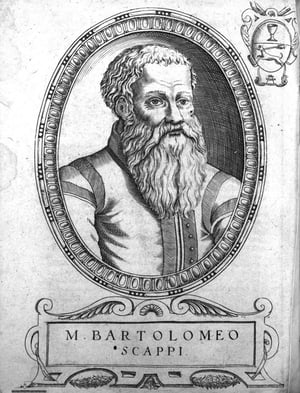

About Bartolomeo Scappi

The World's First Celebrity Chef

Not much is known about Scappi’s life save that he was born in the town of Dumenza in Northern Italy (less than a mile from the current Swiss border) around 1500, that he worked for a handful of Cardinals and popes, that he had a sister named Caterina and a nephew named Giovanni Brioschi, and that he died on April 13, 1577. He was buried in the church of Santi Vincenzo e Anastasio alla Regola, dedicated to cooks and bakers, on the banks of the Tiber River. Upon the demolition of that church in 1888, the cooks and bakers guild moved to the nearby Santa Maria in Grottapinta, on the edge of the Campo dei Fiori. Today, if you walk through the covered passageway next to the now de-consecrated church, you can see a plaque for the guild that recognizes the inspiration of Bartolomeo Scappi.

Not much is known about Scappi’s life save that he was born in the town of Dumenza in Northern Italy (less than a mile from the current Swiss border) around 1500, that he worked for a handful of Cardinals and popes, that he had a sister named Caterina and a nephew named Giovanni Brioschi, and that he died on April 13, 1577. He was buried in the church of Santi Vincenzo e Anastasio alla Regola, dedicated to cooks and bakers, on the banks of the Tiber River. Upon the demolition of that church in 1888, the cooks and bakers guild moved to the nearby Santa Maria in Grottapinta, on the edge of the Campo dei Fiori. Today, if you walk through the covered passageway next to the now de-consecrated church, you can see a plaque for the guild that recognizes the inspiration of Bartolomeo Scappi.

There are a few other small things we know about Bartolomeo Scappi. We know, for example, he dedicated his cookbook to his nephew, Giovanni, who was also his apprentice. We know he left some jewelry for his sister Caterina in his will. There is no record of Scappi’s wife or an indication that he ever married. Records indicate that Scappi worked for Cardinal Marino Grimani in Venice, then later for Cardinal Campeggio and for Cardinal Rodolfo Pio da Carpi in Roma. Based on references from his cookbook, we know he was also intimately familiar with dishes from various locations, including Ravenna, Bologna and Milan, where he may also have lived at some point in his life.

We don’t know exactly when he began working for the papacy; he likely worked for several different Cardinals leading up to when he worked for Pope Pius IV, which we know for certain. He continued to work for Pius V, but Pope Gregory XIII came into office and brought a chef with him, at which point Scappi, an old man, likely retired. He was knighted as Macebearer to the Pope in 1570, under Pope Pius V. The honorary station came with a nice stipend and the responsibility of carrying the mace before the papal coffin.

The Bestselling Cookbook

The foundation for many Italian dishes we love today

Scappi's fame rose to a height when his cookbook L'Opera di Bartolomeo Scappi was published in 1570 and became an instant sensation. In the cookbook, Scappi refers to himself as a “cuoco secreto,” which means “private chef” but translated literally, it reads “secret chef.”

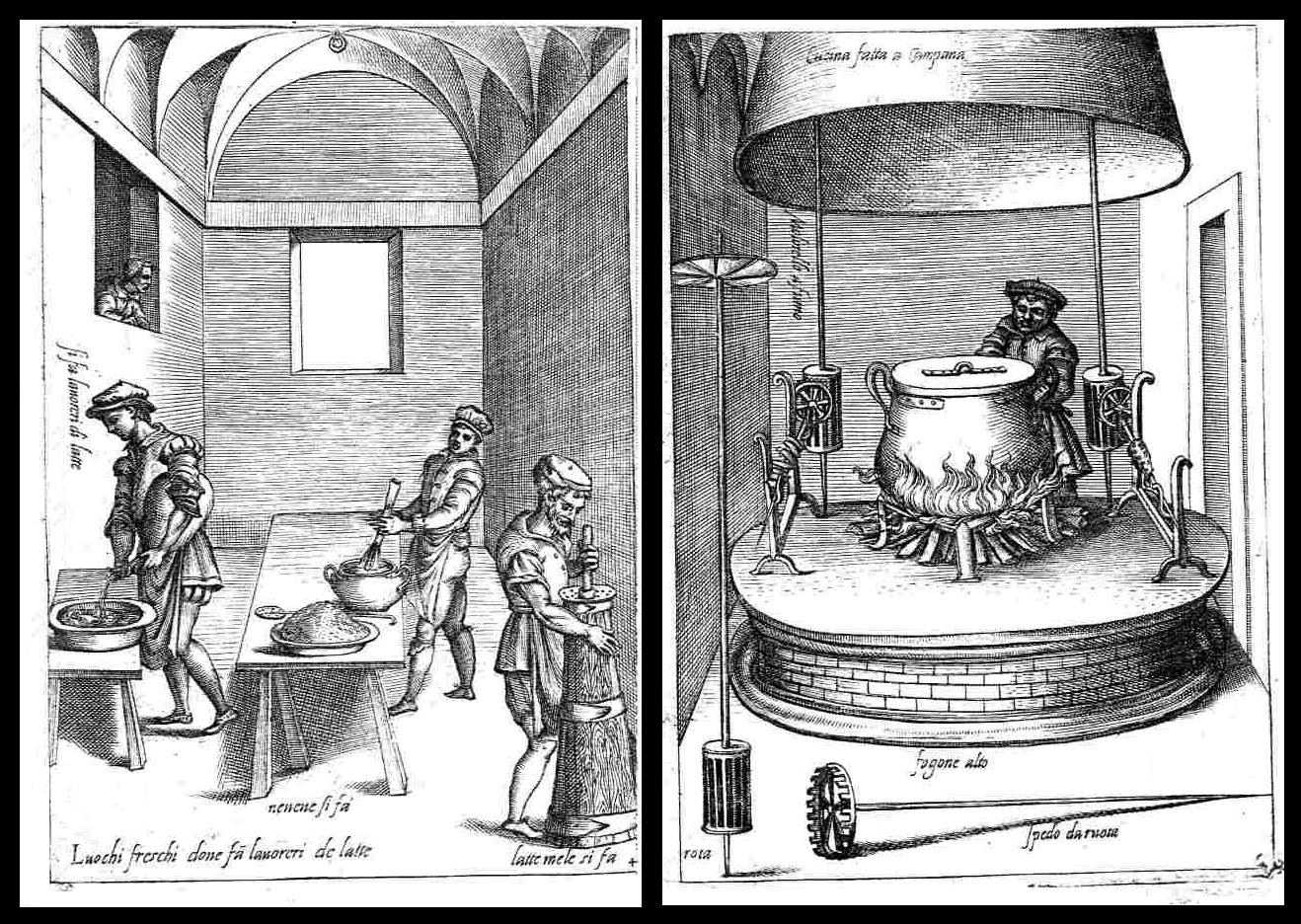

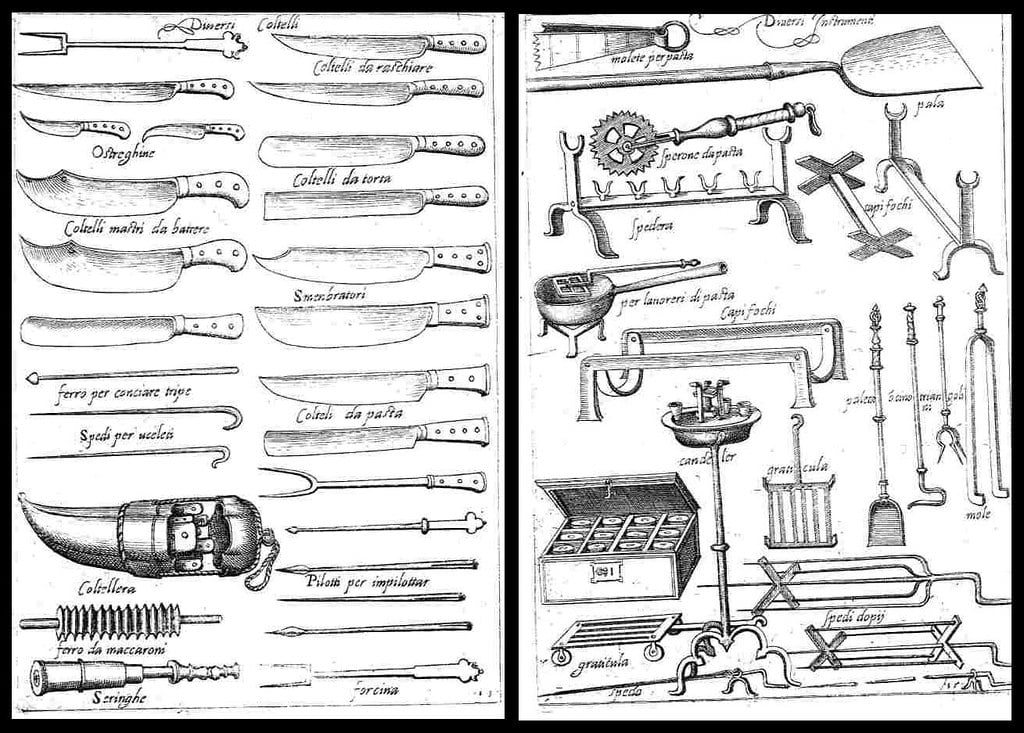

The original book is not a more than a hand’s length long, but it is thick, with over 1,000 recipes and woodcuts that demonstrate cooking tools and techniques. It contains extraordinary insight into the workings of a pope’s private kitchen.

The cookbook is filled with sumptuous recipes and feast menus which glorify the wealth of the princes of the Catholic church. Many of them would be difficult for a home baker to make today purely for the size and scale of the recipes. There are six books in total, plus dozens of woodcuts that show us what the papal kitchens looked like and the variety of pots, knives and utensils used.

The first book of the cookbook is dedicated entirely to his nephew and apprentice, Giovanni Brioschi, giving him all the details of the responsibility of a head chef in a big kitchen. Throughout the book the tone is not just of a teacher to a student, but from a father to a son, one that was being groomed to take on the Maestro’s legacy.

The book has many notable items within its pages. He says that parmesan is the best cheese on earth, that the Jews were cultivating geese for foie gras, and it includes some of the first turkey dishes to be printed in Europe.

Since Scappi cooked for clergy and the Pope, he was very familiar with the need for special seafood-based menus for the over 150 lean or fasting days a year in which no meat could be eaten. There are also numerous recipes for food, broths and potions for the sick. Cooks were often called upon to cure an ailment just as a doctor might be summoned. Scappi also describes how to travel with a nobleman and cook good meals on the road.

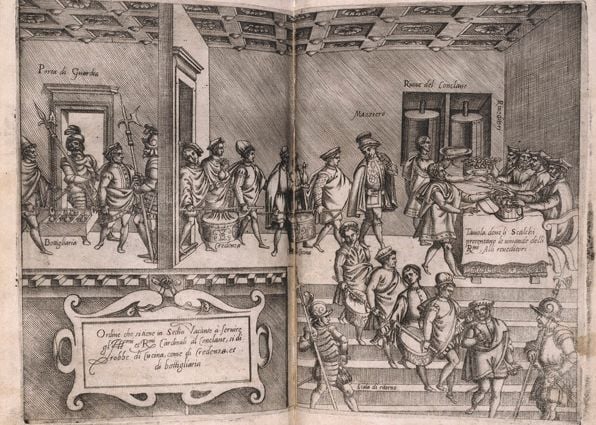

Scappi was also the first person to describe, in great detail, exactly what goes on in a papal conclave. One of the woodcuts in his cookbook even shows how they brought the basket of food to the testers. The big wheels in the wall in the background is where they placed each basket and then spun it around to the cardinals locked in the Sistine Chapel. To learn more about how they chose a pope in the Renaissance, check out my blog post here.

L’Opera of Bartolomeo Scappi was first translated into English by food historian Terrence Scully and published in 2008 by The University of Toronto Press. It’s a much weightier tome than the original, with a great deal of additional commentary and fascinating information to extend the knowledge of the reader. Besides Scully’s translation of the cookbook, I also relied on two other texts for my research about Bartolomeo Scappi: Deborah L. Krohn’s Food and Knowledge in Renaissance Italy, (Routledge, April 2016) and Il Cuoco Secreto Dei Papi: Bartolomeo Scappi E La Confraternita Dei Cuochi E Dei Pasticcieri by June Schino, (Gangemi Editore spa, 2007). Note that the latter text is only available in Italian.

There isn’t a fully inspired modern cookbook based on Scappi’s recipes, unfortunately, but in the sidebar here you'll see a link to the companion cookbook I created for The Chef's Secret, which includes delicious recreations of Scappi's recipes by chefs, food historians, food bloggers and cookbook authors. If you blog, tweet or Instagram your recipes, please tag me or use the hashtag #TheChefsSecret—I’d love to see the results!

Renaissance Italian Food

Cinnamon, sugar and cloves, oh my!

In the Middle Ages, Venice opened the door for the spice trade to flow throughout Europe as trade from the Middle East and Asia began to reach their ports. Pepper was by far the most common spice, but by the 16th century, cloves, ginger, nutmeg and cinnamon became more plentiful, even if prices were still costly. Some of the most common spices include:

- Black pepper

- Cinnamon

- Nutmeg

- Cloves

- Cardamom

- Coriander

- Ginger

- Mace

- Saffron

- Sage

Apothecaries sold a variety of items, not just medicines, sugar and spices. It could be syrups, ink, dyes, paper, paints and cosmetics. Karen Chance tells us, "basically, the division went like this: If something was sold in bulk (like rice), it was the purview of the grocers; if it was fresh foodstuffs (like fish or vegetables), it was sold in open market stalls. But if it was purchased in small amounts, was expensive and/or rare, or was supposed to be consumed for health reasons, it was probably sold by an apothecary."

Recipes during this era were not nearly as heavily spiced as in the Middle Ages, but they would still be a little cloying to modern audiences, relying heavily on rosewater, sugar, pepper, ginger, nutmeg and cinnamon. These flavors make sense in the variety of flaky pastries that are described in Scappi's cookbook, but can be a little more off putting when incorporated into a savory pasta dish. One of the most interesting recipes in the cookbook is that of fried chicken. It's very similar to fried chicken of today, but with the odd flavoring of cinnamon, nutmeg and cloves.

As mentioned earlier, sugar also began to make its way to Italy from the new world. Aside from the wealthy flaunting this spice, it also became nearly ubiquitous in most Renaissance recipes that graced a noble table.

‘Saccharum’ print showing the sugar production process, c. 1580–1605.

To give you a sense of what I mean by ubiquitous, in Scappi's cookbook, over 900 of its 1000 recipes contain sugar in them. There is even an egg recipe that is a simple fried egg, but topped with sugar and a little orange juice!

The Foundation of Foods We Love Today

There are a number of recipes in L'Opera di Bartolomeo Scappi that are familiar to us today or at least form the basis of many foods we find in modern cooking.

For example:

- Pasta - macaroni, tortellini, tortelloni, vermicelli, tagliatelle

- Meatballs

- Pastries - Napoleons, fritters

- Braised beef and stews

- Mushroom and pea soups

- Pies and crostate - pumpkin cheesecake pie, turkey, peach, pear, cherry and apple

- Fried chicken - but brined in vinegar spiced with cinnamon, cloves and nutmeg!

- Ciambelle - (see the image of the ciambelle vendor above). Ciambelle have two forms in today's Italian cooking, the kind that are similar to bagels, and a sweet cookie variety

- Poached eggs

- Foie gras - Scappi mentions that the Jews were fattening up geese.

In Scappi’s cookbook we also see the first recipes that rely heavily on dairy, particularly butter and cheeses. Many of us today are familiar with a recipe first found in L’Opera—zabaglione, a lovely eggy custard dish which is popular as an gelato flavor in Italy too.

Turkey also makes its first appearance in an Italian cookbook in L'Opera. Turkeys found their way to Italy during the Renaissance, but it wasn’t until the latter half of the century that they were deemed suitable for eating. When Spanish and Italian explorers first brought the birds to Europe from the New World, they were regarded as a beautiful and strange oddity, and many nobles kept them as pets or gave them to others as extravagant gifts. Scappi’s cookbook contains the first European recipes for preparing turkey. The sculpture you see here, by Italian sculptor Giambologna, is from 1560.

There are a number of dishes in L'Opera which we might consider to be undesirable (or at minimum, difficult to acquire), including: porcupine, bear, guinea pig, hedgehog, dormouse, crane, peacock, turtle and lamprey eels, to name a few.

Vegetables weren't that common in the cookbook--they were mostly from the ground, and were considered "low" foods. When Scappi does include them, they tend to be in the form of various soups and stews.

They also used all parts of the animals. For example, Scappi describes a particular layered dish to include one layer of calf eyeballs! Savory pies of offal and fish were common (note that even though savory they may have included cinnamon or nutmeg!) as well.

Feed a Cold, Starve a Fever - Dishes for the Sick

Scappi thought that this chapter in his great cookbook was one of his most important, citing the various cardinals and dignitaries he fed when they were ill. Let's take a look at this particular chapter, as it is one of the most fascinating in the cookbook:"It seems to me that I should have done nothing, after having in the five books instructed you about mastering various sorts of dishes suitable for healthy people, had I not shown you as well how to go about making prepared potions, broths, concentrates, pastes, barley dishes and many other preparations needed by the sick and convalescent, all of which preparations I have proved with many gentleman when they have been indisposed..." ~ Bartolomeo Scappi, L'Opera, Book VI, Dishes for the Sick

Potions and concentrates, also considered acque cotte, or cooked water, were usually prescribed by a physician, then fulfilled by the cook. These might be boiled water that has been cooled and flavored by rosewater or they could be water that was heated with steel then filtered, or boiled with a variety of ingredients such as anise, sugar, cinnamon, figs, currants, mastic, barley, chicory or asparagus. Concentrates, on the other hand, were broths, primarily made from chicken, of a variety of thicknesses. One could also make concentrates with an alembic, such as the one pictured here. In the jar on the left, layers of items would be placed inside. In one recipe in L'Opera, for example (Book VI.21), it calls for the flesh of two capon breasts, slices of lemon, egg and sometimes gemstones, gold or other precious metals. Then you would cover this with water and seal the lid, so that steam would only escape from one place, and the resulting reconstituted liquid (In the flask on the right) would then be administered to the patient.

Potions and concentrates, also considered acque cotte, or cooked water, were usually prescribed by a physician, then fulfilled by the cook. These might be boiled water that has been cooled and flavored by rosewater or they could be water that was heated with steel then filtered, or boiled with a variety of ingredients such as anise, sugar, cinnamon, figs, currants, mastic, barley, chicory or asparagus. Concentrates, on the other hand, were broths, primarily made from chicken, of a variety of thicknesses. One could also make concentrates with an alembic, such as the one pictured here. In the jar on the left, layers of items would be placed inside. In one recipe in L'Opera, for example (Book VI.21), it calls for the flesh of two capon breasts, slices of lemon, egg and sometimes gemstones, gold or other precious metals. Then you would cover this with water and seal the lid, so that steam would only escape from one place, and the resulting reconstituted liquid (In the flask on the right) would then be administered to the patient.- Scappi describes a number of broths, including chicken, fish, goat, veal, partridge, pheasant, goak kids' heads and broths in which little meatballs provided additional nourishment.

- Pottages and pates are described in this chapter, including black pudding, an early form of braesola made from veal, and those made from things such as the testicles of a goat, lamb or calves' feet, or perhaps snails, cockles, deboned frogs or even turtles. Sometimes these mixtures, just like the pates of today, were served on slices of bread.

- Gelatins were also common, especially after making so much soup. The gelatins that Scappi describes are savory/sweet, such as one broth made from veal knuckles (which includes a half pound of sugar!) which is reduced till it's "clear as amber" then gelled.

- Barley gruel was considered especially helpful to the sick and Scappi describes several barley gruel recipes including one meant for traveling.

In the section for "thick broths," Scappi describes dishes such as bread pudding, blancmange and zabaglione (in Italian, zabaione), the latter of which he tells us was prescribed for pregnant women in Milan. Unlike the cold dish today, it was served hot in the Renaissance. He also includes a recipe for "grated bread" (VI.73) which is very similar to the Emilia Romagna dish, passatelli, which dates back to medieval times.

In the section for "thick broths," Scappi describes dishes such as bread pudding, blancmange and zabaglione (in Italian, zabaione), the latter of which he tells us was prescribed for pregnant women in Milan. Unlike the cold dish today, it was served hot in the Renaissance. He also includes a recipe for "grated bread" (VI.73) which is very similar to the Emilia Romagna dish, passatelli, which dates back to medieval times. - There are a number of thick soups included as well, including borage, chard, spinach, spelt, chicory, lettuce, purslane, cauliflower, squash, peas, chickpeas, and more.

- Omelettes and fried eggs were very commonly made for the sick and Scappi describes a number of ways to poach eggs in milk, wine and sugar. His recipe for fried eggs is very simple:

Book VI.592 To do fried eggs.

Get fresh eggs. Have fresh butter that is strained so no sediment remains, and heat it up in a frying pan; hold the pan's handle up so the butter runs together and the eggs take on a good shape. Put the eggs into the butter when it is warm and let them cook slowly, splashing hot butter over the yolks without breaking them. Serve them hot with orange juice and sugar over them.

You can do it with melted capon or goose fat. And with the same liquids you can cook them in a small saucepan or tinned copper or silver, or else in silver dishes and serve them in those vessels.

- Scappi's section on pies includes savory (partridge, pheasants, cockerels, veal, fish, goat and lobster) and a bevy of sweet pies such as quince, marzipan, melon, apple, pears, peach and cherry. He describes a squash pie which is very similiar to the pumpkin cheesecake pies of today.

- And finally, Scappi talks a lot about sops. What is a sop? Well, if you have ever heard of the dish "shit on a shingle" you are familiar with sops. Essentially, it's any sort of sauce, sweet or savory, that is served over toast. Interestingly enough, Scappi's savory sops (mushrooms, truffles, legumes) are not included in the dishes for the sick. But the sweet ones? Those were for the invalids, including sops with prunes, plums, verjuice grapes, dates, pears, peaches and cherries.

Le nozze di Cana, Michael Damaskinos 1561 - 1570

Renaissance Italian Recipes

Taste the Flavors of Renaissance Italy

One of the greatest joys of writing a book about Bartolomeo Scappi was having the opportunity to try out the myriad of recipes. Unlike the recipes of Ancient Rome, the foods were much more familiar and the ingredients generally easier to procure. I love visiting Italy now and discovering foods that have its roots in that of the Renaissance, such as when I first had passatelli in Bologna.

To celebrate the publication of THE CHEF'S SECRET, I worked with several chefs, cookbook authors, food bloggers, and food historians to put together a collection of 27 recipes for the home cook, inspired by Bartolomeo Scappi. You can check it out for free here:

Alongside some new re-creations, I include a few recipes from that cookbook on my blog, but with more information:

Sour Cherry Coriander Ice Cream

Lemon Black Pepper Ice Cream with Honey Fig Jam

But don't stop there, here are a few more recipes (either re-creations or inspired modern versions) to whet your appetite for all things Renaissance Italy:

- Zabaglione/Zabaione - via JulsKitchen

-

L’insalata di Caterina – A Renaissance salad - via JulsKitchen

- Visit this page for the following recipes - via La Bella Donna)

- Cabbage Salad From The Fruit (Giacomo Castelvertro)

- Golden Morsels (Platina)

- Frictella from Apples (Platina)

- Saffron Broth (Platina)

- Zanzarella (Platina)

- Torta of Herbs in the Month of May (Platina)

- Torta from Red Chickpeas (Platina)

- Platina's Biancomangiare via Emiko Davies

- Renaissance Elderflower Fritters via Emiko Davies

- Spinach with Raisins (Getty Museum)

- 'Pears' in Broth - via Francine Segan (she also has a recipe in my companion cookbook!)

-

Renaissance Lasagne with Hand-Rolled Pasta - via Splendid Table

- Tortelli - via Grenebroke.com

- Venison Sausage (Scappi) - via Grenebroke.com

- Scappi's pasta dough - Coquinaria

- Medieval Peach Crostata by Inn at the Crossroads

- Scappi's braised beef - Lost Past Remembered (I also have a version of this recipe!)

- From the wonderful Medieval Cookery

-

- Taken from: Scappi, B. (1570). Opera dell'arte del cucinare. Bologna, Arnaldo Forni.

- Taken from: Romoli, D. (1593). La Singolare dottrina di M. Domenico Romoli. Venezia, Gio. Battista Bonfadino.

- Scappi's braised eggplant via Joyce White

- Scappi's spice mix by Jill Norman

- Passatelli by The Pasta Project

- Castlemere Cookies has a bunch of recipes here for the following:

- Fried Cheese (Cascius Fritus)

- Almond Blancmange

- Sicilian semolina w/ grana cheese

- Gnocchi

- Armored turnips

- Asparagus braised and fried with saffron and leek

- Mushrooms blanched and fried with onion and spices

- Kidney beans baked with onions and spices

- Roast Loin of Pork with Red Wine

- Roast chicken with honey/lemon glaze

- Roasted pork with Pomegranate sauce

- Roasted partridge or fowl with pomegranate glaze

- Phyllo, chicken, pork & onions w/saffron

- A spelt and custard torte in crust

- Zabaglione - warm, sweet, soft custard

- Cherry torte

- Ricciarelli (Almond Cookies)

- Sugared almonds (mandorle)

Books and Resources

Books and Resources

Non-Fiction and Fiction about Renaissance Italy

Want to continue your historical adventure to the world of the past? Here are some of my favorite resources on food and the world of Renaissance Italy

Non-Fiction

- The Opera of Bartolomeo Scappi (1570) trans. Terrance Scully

- Il Cuoco Segreto dei Papi by June de Schino (Italian only)

- Food and Knowledge in Renaissance Italy by Deborah L. Krohn

- Cooking and Eating in Renaissance Italy by Katherine McIver

- The Edible Monument, the Art of Food for Festivals by Marcia Reed

- Feast, A History of Grand Eating by Roy Strong

- Daily Life in Renaissance Italy by Elizabeth S. and Thomas Cohen

- The World of Renaissance Italy vol. 1 & 2

- The Banquet-Dining in the Courts of the Renaissance by Ken Albala

Fiction (There are so many...these are a few of my faves)

- Oil & Marble by Stephanie Storey

- The Serpent & the Pearl by Kate Quinn (Scappi is a character!)

- The Lion & the Rose (book 2) by Kate Quinn

- The Gondola Maker by Laura Morelli

- Appetite by Phillip Kazan

- The Most Beautiful Woman in Florence by Alyssa Palombo

- The Scribe of Siena by Melodie Winawer

- The Orphan of Florence by Jeanne Kalogridis

- The Birth of Venus by Sarah Dunant

- Tigress of Forli by Elizabeth Lev

- The Chef's Apprentice by Elle Newmark

The Chef's Secret

|

|

| THE CHEF'S SECRET, the second historical novel by Crystal King, is set in Renaissance Rome, detailing the mysterious life of one of the most famous chefs in history. Bartolomeo Scappi was the private chef to four Popes and the author of one of history’s best selling cookbooks. His nephew and apprentice, Giovanni, is on a quest to find out the truth about his uncle and the fifty-year love affair that the chef hid from the world. |

THE CHEF'S SECRET is a fictional retelling of the life of Bartolomeo Scappi, who lived in sixteenth century Rome. When his cookbook, L’Opera, was published in 1570, it became the world’s best-selling cookbook for the next two hundred years.