How did I end up writing a gothic novel (In The Garden of Monsters) about Persephone (although I use the Roman name, Proserpina) and how on earth did Dalí end up in it? Flashback to the middle of the pandemic when I was struggling to sell a novel about a Renaissance meat carver. “Renaissance books aren’t selling right now,” I was told (not long before Maggie O’Farrell’s The Marriage Portrait hit the bestseller list). I was discouraged. This sentiment also didn’t bode well for the book I was writing about the obscure Baroque steward Antonio Latini. I was lamenting about the whole thing on Zoom with an author friend, Kris Waldherr. “If I were going to write something that would actually sell, what would it be?” I remember her tilting her head in thought. “Well, gothics are hot right now (says the author of the gothic masterpiece Unnatural Creatures).” And I thought to myself, hmmm. If I were to write a gothic, what would I write?

Immediately, the location came to me. And if you’ve read many gothics, you know it’s all about the location. I had been to the town of Bomarzo, an hour north of Rome, a couple of years before, completely on a whim only because it was near Caprarola, which I was visiting for my work on that Renaissance meat carver book. In Bomarzo is a spectacular Mannerist garden of sixty-six stone monsters called Il Sacro Bosco, or the sacred wood. It has a fascinating history that begins in the late 1500s, then pauses for nearly 400 years, when the whole garden is abandoned and overgrown and then rediscovered by poets and artists in the early 20th century. In the 1950s, a couple bought it and restored it for the public to visit. The garden is certainly beautiful, magical, strange, and somewhat creepy, but looming above it on the hill is the medieval palazzo, making it an extra perfect setting for this ghosty story.

During the Renaissance period in Italy, the creation of fantastical gardens was a significant reflection of the era's artistic and intellectual awakening, particularly in the Lazio region, which encompasses Rome and the towns surrounding the city. These gardens, like the Villa d'Este in Tivoli, Villa Farnese in Caprarola, and Villa Lante in Bagnaia near Viterbo, were not just about aesthetic beauty but also served as manifestations of philosophical and mystical ideas. They featured elaborate sculptures, fountains, and grottoes, each symbolically intertwined with myths, allegories, and classical references. These gardens emphasized creating a harmonious blend of art and nature, inviting visitors into a world where the real and the surreal merge. The Villa d'Este, renowned for its innovative water features and artistic design, the geometrically precise and architecturally integrated Villa Farnese, and the mannerist, surprise-laden layout of Villa Lante, each in their own way, embodied the Renaissance fascination with blending artistic imagination with the natural world.

Nestled among the wooded hills of Bomarzo, Italy, lies a garden unlike any other of its era or beyond. The Sacro Bosco ("Sacred Wood"), also known as the Park of the Monsters, was created by a wealthy nobleman named Vicino Orsini. It forsakes manicured lawns and symmetrical flowerbeds for a realm of the bizarre. Giant sculpted monsters lurk within the foliage, a building leans at a precarious angle, and inscriptions offer cryptic riddles rather than guidance. The Sacro Bosco stands as a testament to Mannerism, a movement that defied both rational explanation and classical aesthetic norms.

Table of Contents

.jpg)

Who Was Vicino Orsini?

Pier Francesco Orsini, better known as Vicino Orsini (1523–1583), was an Italian condottiero, patron of the arts, and the Duke of Bomarzo, famous for commissioning the Mannerist Park of the Monsters, or Sacro Bosco, in Bomarzo, northern Lazio. Born into the prominent Orsini family in Rome, Vicino was the son of Giovanni Corrado Orsini and Clarice Orsini. His inheritance of the duchy of Bomarzo in 1542 came after a heated dispute with his younger brother, Maerbale. The matter was settled in his favor by his influential friend, Cardinal Alessandro Farnese, who is honored with plaques within the garden. The contested inheritance also included the centuries-old palazzo in Bomarzo and its surrounding lands, which became central to Vicino’s legacy.

Following his father's path, Vicino pursued a military career as a condottiero, a mercenary soldier who offered his services to the highest bidder. Over more than a decade, he fought on behalf of Cardinal Farnese and his father, Pope Paul III, as well as later for Pope Julius III and Pope Paul IV. His military career was marked by several notable moments, including being taken prisoner twice and released. Despite his martial endeavors, Vicino was known for his intellectual and artistic interests. He spent time in Venice’s intellectual circles, forging friendships with scholars like Francesco Sansovino, and maintained a romantic and hedonistic lifestyle. He was a lover of food, literature, and philosophical discourse, and his correspondence reveals a man deeply engaged with the cultural and intellectual currents of his time.

Vicino married Giulia Farnese in 1545, aligning himself with one of Italy’s most powerful families. Giulia, not to be confused with her infamous great-aunt of the same name, who was the mistress of Pope Alexander VI, was the daughter of Galeazzo Farnese, Duke of Latera, and Isabella dell'Anguillara. Their marriage, blessed by family ties to the Farnese lineage, was marked by both affection and strategic importance. Although Vicino was known to have several passionate lovers, both during his marriage and afterward, he nonetheless dedicated his famous garden, the Sacro Bosco, to Giulia’s memory following her death, possibly in 1560 or 1564. This dedication, however, may have been more a gesture of respect to the Farnese family and recognition of Giulia’s capable management of his estates during his military absences than a symbol of undying love. In his letters, Vicino expressed gratitude for the freedom to have multiple romantic relationships.

The Sacro Bosco, or Park of the Monsters, is perhaps the most enduring testament to Vicino’s complex personality and interests. Created starting in 1547, the garden is filled with bizarre sculptures, carved directly into the natural landscape. These sculptures—featuring fantastical creatures, mythological figures, and cryptic inscriptions—reflect Vicino's fascination with the esoteric, the surreal, and the intellectual currents of his time. The park served as a statement to his peers, showcasing his wealth, taste, and intellectual curiosity. The little wood, or "boschetto," as he affectionately called it, was a marvel of its time, intended to stimulate wonder and contemplation among visitors.

Vicino retired to Bomarzo later in life, where he surrounded himself with artists and writers, leading an Epicurean lifestyle that celebrated pleasure and intellectual exploration. He and Giulia had five sons—Corradino, Marzio, Alessandro, Scipione, and Orazio—and two daughters, Faustina and Ottavia. His children carried on the family legacy, with his son Orazio dying heroically in the Battle of Lepanto in 1571, and his daughters making prominent marriages that continued the Orsini influence in Italy.

IMAGES:

1.Portrait of a Young Man (thought to be Pier Francesco Orsini, by Lorenzo Lotto, 1530

2. Medallion by Pastorino dei Pastorini of Vicino Orsini in profile around 1550.

3. The bear and rose are the symbols of the Orsini family. This was taken by Crystal King in the Sacro Bosco garden, 2023.

From Chapter 3 - IN THE GARDEN OF MONSTERS

Ignazio started down the thin, overgrown trail. He stopped when we were a few dozen or so paces away from the dirt parking area. “Now we are officially in the garden of monsters,” he warned us with a dark grin. “They’re monsters made of stone, but sometimes the creatures may appear quite sinister. Worry not. For the most part, you have nothing to fear.”

I couldn’t tell if he was joking or not. Considering the green glow I had seen the night before, he might not be jesting after all.

“Have you had to rescue many of your guests?” Gala asked, her tone teasing.

“You are the first visitors we’ve had in years, though there are curious trespassers on occasion.” Ignazio pointed down the path ahead. “This is a back passage into the Sacro Bosco or, as it is often called, the boschetto, the little wood. The original main entrance, now unused, is on the other side of the garden. There you’d have been greeted by two worn sphinxes, one of which bears an inscription that reads ‘You who enter here put your mind to it part by part and tell me then if so many wonders were made as trickery or art.’”

“So, the statues are riddles to decipher?” Jack asked.

Ignazio gave him a brilliant smile. “Or are they just art? Come, let us find out.”

I fell in step behind him, marveling that we were walking along paths that were centuries old. The air felt charged with magical energy, although I was sure it was only my excitement to be sitting for Dalí. Then I stumbled, nearly crashing into Gala, who grunted as I used her arm to steady myself. Regret washed over me for having worn my best pair of heels; it was an attempt to make an impression. And indeed, an impression was being made, but not in the way initially intended.

A bleat emanated from somewhere deep in the garden. “That didn’t sound like a monster,” Jack remarked.

“There are a few locals who let their sheep graze near here,” Ignazio explained. “They think the monsters scare away the wolves.”

Jack and I exchanged looks. He clearly thought the same as I—Italian superstitions truly made no sense.

“Wait,” I called out to Ignazio as he started forward. “We were told that the locals are afraid of this place, because of a woman who died in the garden. Is that true?”

“Yes. A long time ago. Several women are rumored to have died in the garden. The details are lost to history, but superstition remains long in the mind.” Ignazio’s eyes did not leave mine as he spoke, and it was as though he was imploring me to discern some hidden meaning in his words.

My heart skipped a beat.

“It’s a shame,” he continued. “The boschetto was once a place of great wonder and beauty that was much talked about among the Italian nobility.”

“Are there ghosts?” Jack asked, elbowing me playfully in the ribs.

“Perhaps.” A fire seemed to light in Ignazio’s eyes, but he said no more.

Jack elbowed me again. “I told you there were ghosts.”

I gave him a little chuckle, but it was a nervous laugh.

The Garden

Orsini enlisted the help of Pirro Ligorio to design the garden, and the sculptures are attributed to Simone Moschino. Ligorio was the renowned architect behind the gardens at Villa D’Este in Tivoli, and he worked on St. Peter’s in Rome after the death of Michelangelo. The sculptures themselves were likely created by several workers led by sculptor Simone Moschino, the son of Francesco Moschino, who helped Vicino redesign parts of Palazzo Orsini upon the hill above the garden.

The Sacro Bosco once had an artificial lake that was created by damming up the stream that ran through the garden. This lake helped feed the numerous fountains that are scattered throughout the boschetto. This lake no longer exists, but archaeological evidence of its location has been discovered.

Scholars are still debating the hidden meanings behind the development of the specific statues and their placement in the garden. It is possible that at least portions of the garden were inspired by Ludovico Ariosto’s epic poem Orlando Furioso, as well as the mysterious text, Hypnerotomachia Poliphili (in English, Poliphilo’s Strife of Love in a Dream), thought to have been written by Francesco Colonna. Vicino was enamored by the Stoics and the ancient Greek philosophers and was likely also influenced by the works of Dante and Petrarch. There is some thought that the garden is laid out according to particular alchemical theories, and that the sculptures pertain to the stages of transmutation, that of turning ordinary metals into gold, which was also a metaphor for human transcendence.

Amidst the garden's wonders, key sculptures demand attention. The gaping maw of the Ogre, also known as the Orco, represents an entrance to the underworld and confronts visitors with the grotesque embodiment of death. There is a stone table inside the mouth of this monster, which, when viewed from the orco’s exterior, looks very much like a tongue. Inscribed above the monster’s mouth are the words Ogni Pensiero Vola—All Thoughts Fly. This likely echo’s Dante’s words in The Inferno, “Abandon all hope, ye who enter here.” It also references the phenomenon that words spoken in the mouth of the monster may be heard from down the path. The orco originally had four teeth, two on top and two on the bottom. There is a photo of Salvador Dalí sitting on one of the bottom teeth with its partner tooth missing. For public safety, it seems that the remaining bottom tooth was removed when the garden was restored.

The statue of Proserpina, or Persephone, is a massive stone bench that faces down a green hippodrome lined with stone pinecones. Her lower body becomes the bench, and her arms look posed to wrap around any who sits upon it. She is eroded and moss-covered today but must have been quite regal in the garden’s original incarnation.

The twisted house, defying architectural logic, adds a sense of disorientation and symbolizes a world thrown off-balance. It is a two-story building that leans against a wall, and a short bridge leads from the upper level of the garden to the top floor. There are windows, but they have never held glass. It is extremely disorienting to stand and walk in the tiny rooms of the house.

The battle of giants is one of the most striking and memorable sculptures in the garden. This particular sculpture depicts a dramatic battle scene between two giants, creating a powerful visual narrative that captures the viewer's imagination. It shows one giant overpowering the other, with the victor seemingly emerging from the ground to grasp his opponent in a fierce embrace. The figures are rendered with exaggerated features and expressions, characteristic of the Mannerist style that pervades the garden. The muscles are tensed, and the faces are contorted in expressions of rage and agony, conveying the intensity of their struggle. The statue serves as an allegory for the internal battles that humans face, such as the struggle between good and evil, or the fight against one's own demons. The size and dynamism of the sculpture make it a focal point within the garden, drawing visitors into its dramatic story. The giants' statue, like many of the sculptures in the Sacro Bosco, is open to interpretation. It has been suggested that it could represent the mythological battle between Hercules and Cacus, a fire-breathing giant, or more likely, as the plaque nearby suggests, it could represent Ludovico Ariosto’s character, Orlando Furioso, in the fight with the woodsman. However, research laid out by Horst Bredekamp suggests that the giants were not both men, but that it was possibly depicting the rape of an Amazon (who would lack breasts and therefore was misidentified previously as a man). Obviously, for the purposes of the story, the idea that it was Orlando Furioso wrestling with a woodsman made more sense.

Vicino Orsini died in 1584, and while his sons likely inherited the palazzo and garden, they seem to have been unable to fund its upkeep. The holdings were sold to the Lante Della Rovere family in 1645 and to the Borghese family in later years, but for the better part of five centuries, the Sacro Bosco was neglected and overgrown. Statues toppled over and eroded, and the lake dried up. There was once a wall around the garden, and it too has vanished, the stones likely ending up as part of the homes up on the hill.

In The Garden of Monsters attempts to stay true to the garden’s layout as it would have been in 1948 when Dalí visited, before the Bettini family moved a few of the sculptures (such as the sphinxes at the entrance), and when it was still wild and overgrown. There were fewer trees then than there are today, and there is no proliferation of wild pomegranate bushes, but this is where poetic license came in to help shape the story.

Today, the Sacro Bosco draws visitors from around the world. Its monsters, its leaning house, and its enigmatic symbolism continue to fascinate and bewilder. While modern art historians analyze its place within the broader Mannerist movement and seek to unveil hidden meanings, casual visitors, too, are captured by the sheer power of the bizarre. Walking through the Sacro Bosco is a departure from the ordinary. It is a journey into a world of deliberate artifice, where the strange and grotesque confront us with unsettling questions about our own nature, fears, and place in an incomprehensible world. The garden remains a living riddle, offering no easy answers but inviting endless possibilities for exploration and introspective wonder.

IMAGES:

1. The orco, or ogre. Inside his mouth is a table that looks very much like a tongue. Above its mouth says "Ogni pensiero vola" or "All thoughts fly" which refers to the acoustical trick of hearing people speak within the mouth of the monster from down the path.

2. Ceres, or Demeter

3. Cerberus who is guarding the entrance to the Underworld

4. Proserpina (Persephone)'s bench and Crystal King

5. The giants

6. A dragon fighting off a lion and wolf

From Chapter 4 - IN THE GARDEN OF MONSTERS

“So, why do you think Vicino Orsini created so many monsters to represent death and the Underworld?”

Jack laughed. “We humans are all obsessed with money, sex, and death, aren’t we? But wait, you ain’t seen nothin’ yet.”

There weren’t many trees in that part of the boschetto, and two statues were visible a few paces ahead of us—a monstrous elephant with a castle on its back, and a bizarre, doglike dragon fighting off lions. As we neared, I could see Dalí had mounted the elephant and stood in its castle, holding an arm out, pointing the beast forward. Paolo was at its base, filming.

“We’re up here,” I heard Gala say. It sounded like she was right next to me, but when I whirled about, I didn’t see her anywhere. Jack nudged my arm and pointed up a path toward a gigantic face, its mouth wide open in a scream. I gasped. This must be the screaming ogre that Dalí mentioned yesterday. Gala stood inside the mouth of the monster, below its two stone teeth, waving at us.

“But I could hear her perfectly,” I said in awe.

“An acoustic trick that Ignazio showed us. Killer-diller, huh? Come on—there is a mountain of food up there.”

We made our way up the dirt trail to the orco. Pomegranate bushes laden with fruit flanked the stone of the monster’s cheeks, the surrounding ground littered with half-eaten fruit. As we approached, I saw it had a tongue—a table carved from peperino. Above the mouth was an inscription: OGNI PENSIERO VOLA. All thoughts fly. Or at least anything said in the mouth of this ogre.

Exploring the Garden

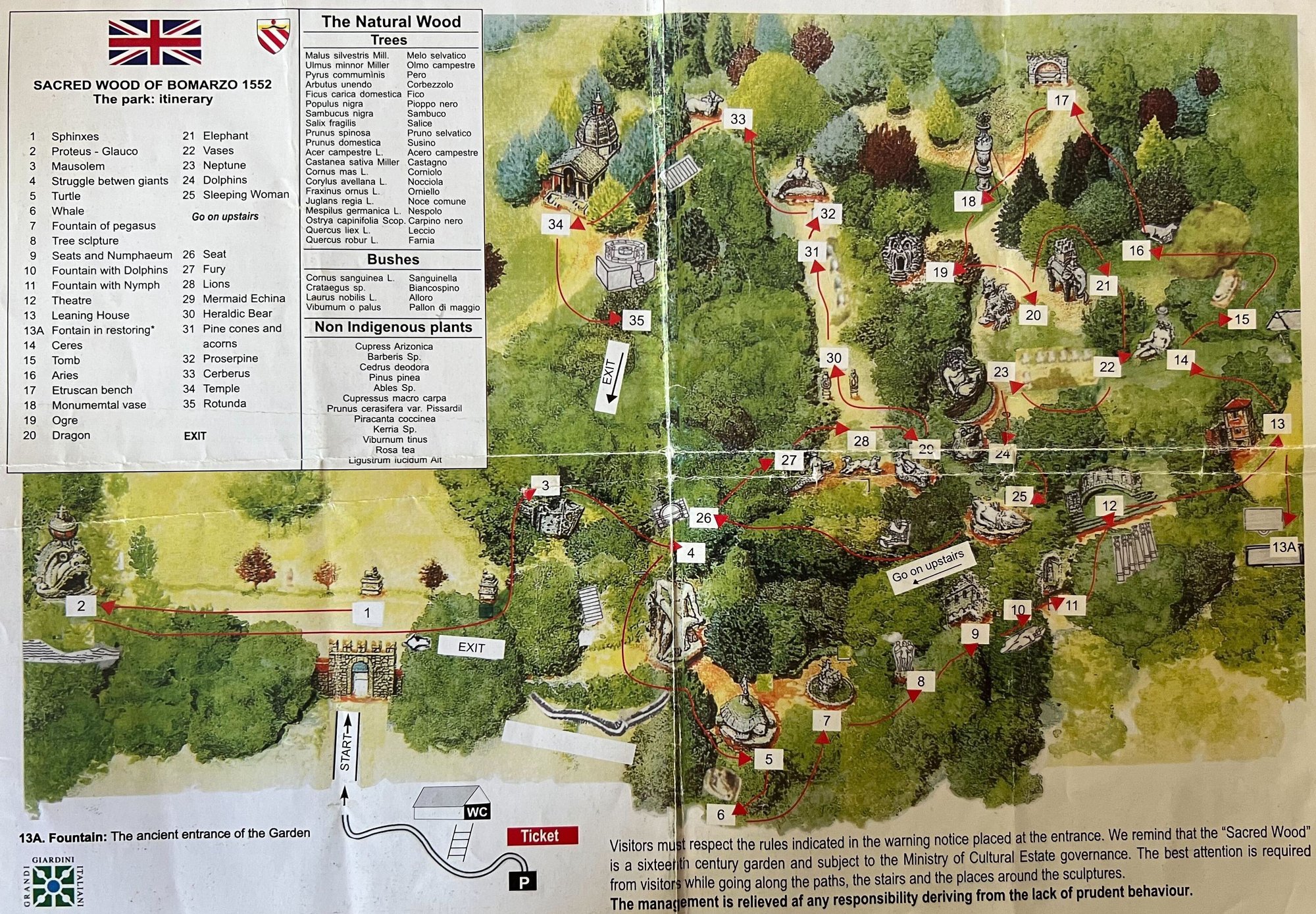

When you visit the garden, you are presented with a map that tells you want the statues are. As you can see, I've worn this one a bit thin because I referred to it so often when writing IN THE GARDEN OF MONSTERS. You'll notice that there are no pomegranate trees listed here (punica granatum), so I took a bit of liberty in adding them. The tree is, however, readily found in parts of Italy.

One of the strangest features of the garden is this indention carved into a rock in a part of the garden much less traveled. It's often referred to as the Etruscan tomb and you'll notice on the map above it just says "tomb." Scholars are unable to date the creation of the tomb.

It may be an ancient Etruscan tomb. There are many Etruscan sites scattered all over the Tuscia region, and it is possible that this is some long forgotten remnant.

But it's equally possible that it's a feature that Orsini added to the garden himself, as recreating the ancient past was in vogue over the years, and perhaps he created it as a way to wow his guests.

A pivotal scene in my novel happens at the site of this tomb.

The Statues

This is the rock where Julia first hears whispers in the garden.

This fountain has a statue of Pegasus in the center, its hoof striking a rock that symbolizes Mount Helicon. This action brought forth the spring of Hippocrene, the fount of inspiration sacred to the Muses.

This is an orca - the head of a whale emerging from within the waters of a stream.

Across from the Pegasus sculpture is a giant tortoise. Upon its back is the figure of Fame, atop a globe. She once held a set of double horns, now gone.

This is part of the Nymphaeum, an area that once had a vaulted roof. It was purposefully designed to look like an ancient ruin. The inscription reads: "The cave and the fountain free you from every dark thought."

Poseidon (Neptune), god of the oceans and rivers, and brother to Hades/Pluto. Below him is a now empty pool of water. An orca rears up to his side.

A siren.

Many Schools of Thought

Scholars are divided on the meanings behind the sculptures in the Sacro Bosco. Some interpret them as allegorical representations of philosophical ideas, while others believe they are whimsical creations meant to evoke a sense of wonder and mystery. The lack of definitive historical records further complicates the debate, leaving room for a wide range of interpretations and theories. Some experts argue that the sculptures reflect the personal beliefs and experiences of the park's creator, while others suggest broader cultural and artistic movements influence them.

As I mentioned before, Some scholars even argue that there are alchemical ties to the interpretations of the sculptures in the Sacro Bosco. They suggest that the park's figures and symbols are imbued with alchemical significance, representing the transformative processes of alchemy, such as the transmutation of base metals into gold or the quest for the philosopher's stone. These interpretations delve into the esoteric and mystical aspects of the sculptures, proposing that they serve as a coded alchemical text, guiding the initiated through the stages of spiritual and material transformation. This perspective adds yet another layer of complexity to the already multifaceted debate, highlighting the rich tapestry of meanings that the Sacro Bosco continues to inspire. To learn more about this, check out the video below.

To learn more about Bomarzo, check out these two videos. The first is a wonderful little documentary. The second is a drone video and walkthrough of Palazzo Orsini.

Dalí in Bomarzo

I shared this on my page about Dalí , but in case you haven't seen it yet I wanted to make sure it was included here.

In The Garden of Monsters takes place in 1948, after Dalí and Gala had returned to Europe. In the fall of that year, Dalí went to Rome to paint sets for the Rome Opera. While he was there, he caught wind of a strange garden, the Sacro Bosco (Sacred Wood), just an hour north of Rome.

Dalí, who was deeply influenced by surreal and dreamlike imagery, found a kindred spirit in the bizarre and imaginative sculptures of Bomarzo. His visit to the park reinforced his fascination with the surreal, and he even cited the park as an influence on some of his later works. The grotesque and distorted forms in Bomarzo aligned perfectly with Dalí's own artistic vision, which often sought to challenge reality and embrace the fantastical.

Dalí was particularly captivated by the Orco (Ogre), a large stone sculpture of a monstrous face with an open mouth that visitors can walk through. This structure, with its inscription "Ogni pensiero vola" ("Every thought flies"), resonated with Dalí’s belief in the power of the subconscious mind and the surreal. The park's mysterious and otherworldly atmosphere likely inspired Dalí's own explorations into the bizarre and the uncanny, and he reportedly visited Bomarzo multiple times, drawing inspiration from its unique blend of nature and art.

While he was at the Sacro Bosco, Dalí decided to film a little three-minute movie:

From Chapter 3- IN THE GARDEN OF MONSTERS

Farther down the footpath, we came to another fork, three thin trails in the brush. One of the forks led down a perilous set of stairs. On that lower trail, an enormous head rose above the stone retaining wall. Dalí gave a cry of excitement before charging down the steps, and we followed after him. As we neared, we could see the giant held another man upside down by the legs. The giant’s face was well wrought, etched with lines. His hair was curled, and his carved beard was lush and full. His body was thick with muscle. The man he held showed his agony, his mouth open in a scream, his eyes empty and wide. Gala knelt to pick the moss off his face.

“There is more going on here!” Dalí went close to the statue and pointed up between the two stone men.

Indeed, it did look as though the giant might be performing some intense sexual act upon the other man.

Ignazio pointed to a partially eroded plaque on the nearby wall. He put his finger on the word Anglante.

“If you know Ariosto’s epic poem, Orlando Furioso, then you know that Orlando was the Lord of Anglante. The story is that Orlando was driven mad when the beautiful Princess Angelica did not return his love. In his fury, he raged through the land, destroying anything in his path. In this vengeful state, he met two woodsmen with a donkey pulling a cart of logs. Rather than waiting for them to move aside, he kicked the donkey so hard it landed over a mile away. Then he took one of the terrified woodsmen by the legs and tore him in half. And clearly, you can see here the giant is ready to tear this man in two.”

Ignazio paused to watch Gala stroke the tortured man’s face. When he continued, his voice took on an ominous tone. “This is one of my favorite statues in the garden. I think of it as a warning, that passion may render love into something evil. It can light the fire of desperation, anger, or even hate.”

Ignazio looked off into the depths of the garden. I followed his gaze through the greenery but did not see anything. I wondered who among us this warning was for—it seemed more than just a story to me.

Dalí startled me with a shout. “Paolo, get your camera!”

Dalí and Gala posed with the giants, then motioned for me to come forward so Paolo could take a couple of photos of me standing next to the statue before we went back up the crumbled stairs.

The Restoration

Vicino Orsini died in 1583, and while his sons likely inherited the palazzo and garden, they seem to have been unable to fund its upkeep. The holdings were sold to the Lante Della Rovere family in 1645 and to the Borghese family in later years, but for the better part of five centuries, the Sacro Bosco was neglected and overgrown. Statues toppled over and eroded, and the lake dried up. There was once a wall around the garden, and it, too, has vanished, the stones likely ending up as part of the homes up on the hill.

In the early part of the twentieth century, news of the strange place reached the ears of many writers and artists of the time, and it was visited by the likes of Italian art critic Mario Praz, poet and novelist Jean Cocteau, and several others of the Surrealist movement, including, of course, Salvador Dalí. By this time, most Bomarzo villagers avoided the location due to rumors of a woman dying there centuries past. Still, the farmers whose land abutted the boschetto let their sheep graze among the statues. Dalí made a little film about the boschetto, and it took the world by storm. In the film, he walks into the tempietto with a white cat on his shoulders, an inspiration for the inclusion of Orpheus in the novel.

A few years after Dalí’s visit, in 1954, Giovanni Bettini purchased the land from the Borghese family and, after an exorcism to banish any lingering evil spirits, restored it, enabling thousands of visitors to experience the garden every year. His wife, Tina Severi Bettini, died in an accident during the restoration process, and she and Giovanni are now memorialized in the tempietto. There is no evidence that Giulia Farnese was ever interred there.

Visiting Bomarzo

It’s possible to visit the garden, often called the Parco dei Mostri (Monster Park), now maintained by the Societa Giardino di Bomarzo.

The town of Bomarzo is a little over an hour north of Rome (105 Km). It's easiest to reach the town by car. If you go by train you'll need to catch a bus to Bomarzo from Orte Scalo Station.

The park is open every day from 9AM to 5PM in Nov-Feb, 9AM to 7PM March-Sep, and 9AM to 6PM in October. Last entry is one hour before closing time.

You can purchase tickets in person, or online. €13 for adults or €8 for children ages 4-13.

Visit the Sacro Bosco website here.

Books and Resources

LEARN MORE ABOUT The Sacro Bosco Garden

There aren't many books about the garden, and some of them are difficult to acquire, but if you really want to satiate your hunger to learn more about this fascinating place, here are some recommendations:

NOVELS

- Signatures in Stone, A Bomarzo Mystery by Linda Lappin

- Dante's Garden: Magic and Mystery in Bomarzo by Teresa Cutler-Broyles

- Bomarzo by Manuel Mujica - Lainez

-

Michelangelo's Ghost (A Jaya Jones Treasure Hunt Mystery Book 4) by Gigi

For Children

- The Sacred Wood of Bomarzo - Coloring Book by Federica Bettini

- The Sacred Wood of Bomarzo by Daniele Petretti

Reference

Bomarzo and the Sacro Bosco

- The Garden at Bomarzo by Jessie Sheeler (in English)

- The Monster in the Garden: The Grotesque and the Gigantic in Renaissance Landscape Design by Luke Morgan

- Vicino Orsini il Sacro Bosco di Bomarzo by Horst Bredekamp (in Italian)

- Bomarzo Il Sacro Bosco Fortuna Critica e Documenti by Sabine Frommel (in Italian)

- A Dream of Etruria: The Sacro Bosco of Bomarzo and the Alternate Antiquity of Alto Lazio, a research paper by Katherine Coty

Books and Resources for the Tuscia Region of Italy

Mary Jane Cryan is an expert on this region, and has a number of excellent resources for the discerning learner/traveler:- Elegant Etruria website

- The Painted Palazzo -Mary Jane's blog

-

Etruria—travel, history, itineraries in Central Italy - Mary Jane Cryan

Additional resources

- Etruscan Places: Travels Through Forgotten Italy - D.H. Lawrence

- A world of mysterious journeys in Italy:Tuscia Viterbese by Marco Menichelli

- VITERBO and the towns of Tuscia by Demetrio Piccini

- Insider's Guide to Tuscia - The Italy Insider

-

This Under-the-Radar Region Has Some of Italy's Best Sights - Fodor's Travel

BUY IN THE GARDEN OF MONSTERS NOW

Julia Lombardi is a mystery even to herself. The beautiful model can’t remember where she’s from, where she’s been, or how she came to live in Rome. When she receives an offer to accompany celebrated eccentric artist Salvador Dalí to the Sacro Bosco—Italy’s Garden of Monsters—as his muse, she’s strangely compelled to accept. It could be a chance to unlock the truth about her past…

IN THE GARDEN OF MONSTERS is a retelling of the myth of Hades and Persephone, inspired by Salvador Dalí's 1948 visit to the Sacro Bosco Mannerist statue garden.

“Inventive spin on the Hades and Persephone myth… King makes the familiar tale feel fresh with her unusual and enthralling setting, which eerily blurs the real and the surreal. This is an exciting reinterpretation.” ~ Publishers Weekly