Salvador Dalí's meeting with Gala in 1929 was as surreal as the art he would later create. During the summer of that year, Dalí invited a group of Surrealist friends to his family home in Cadaqués, Spain. Among the guests were poet Paul Éluard, his wife Gala, filmmaker Luis Buñuel, and artist René Magritte along with his wife Georgette. Dalí, eager to make an unforgettable impression on Gala, devised a bizarre plan that epitomized his eccentric nature. In preparation, he meticulously tore his shirt and then smeared his chest with a mixture of laundry bluing, rust stains, and blood. Not content with just this, Dalí shaved his armpits, rubbed them with the concoction, and intentionally made himself bleed, creating bluish streaks down his sides.

To complete the spectacle, Dalí applied aspic oil to his body, mixing it with fish glue and the foul-smelling odor of ram dung. He also adorned himself with a string of pearls and tucked a fiery-red geranium behind his ear. This grotesque and theatrical transformation was his way of embodying the "savage state," which he believed was necessary to capture Gala’s attention.

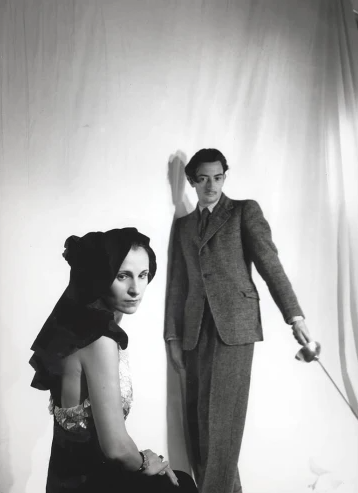

When Dalí finally went to meet Gala, the result was a bizarre spectacle. His intentions were to appear as a "regular savage," in his own words. However, upon seeing his reflection before meeting her, Dalí realized the extent of his oddity, lamenting that he looked "like a regular savage" and yet detested it. Despite this initial reaction, Gala, who was ten years older than Dalí and married to the poet Paul Éluard, was intrigued by Dalí's wild behavior and intense personality. Gala, already known for her liberated sexual life—having engaged in a ménage à trois with Éluard and the artist Max Ernst—was drawn to Dalí's eccentricity. Despite the unusual first impression, they quickly formed a deep and intense connection, with Gala becoming not only Dalí's muse but also his life partner and manager. Their relationship, marked by both passion and pragmatism, would define much of Dalí's later life and career.

Gala’s influence on Dalí's art was profound and multifaceted. She was not just a muse but a critical force in his creative process. Gala became a recurring subject in Dalí’s work, often depicted in a mystical or religious light, such as in his early surrealist works like The Great Masturbator (1929) and Dream caused by the Flight of a Bee Around a Pomegranate (1944). She inspired Dalí’s exploration of themes like eroticism, obsession, and the subconscious. Under Gala’s influence, Dalí refined his technique, merging meticulous draftsmanship with surreal, dreamlike imagery. Her presence helped him transition from the playful absurdities of his early work to the more profound and unsettling themes that would define his mature surrealist phase.

Gala also played a crucial role in shaping Dalí’s public persona. She encouraged his flamboyant and often shocking behavior, which became as much a part of his art as his paintings. Gala’s guidance helped Dalí navigate the art world, turning him into a global icon of surrealism. Her managerial skills ensured that Dalí’s work was widely exhibited, securing his place among the most important artists of the 20th century.

Gala herself was an enigmatic and complex figure, often described as both magnetic and manipulative. She possessed a sharp intellect and a commanding presence, which she used to assert control over those around her. Gala was fiercely independent, driven by a desire for freedom and personal fulfillment. This independence manifested in her relationships, where she maintained a degree of emotional distance, even with Dalí. While deeply involved in Dalí’s career, she was also known for her own artistic pursuits, contributing to surrealist projects and cultivating relationships with other artists. Gala’s dual nature—both nurturing and domineering—made her a formidable partner for Dalí, and her influence over him was undeniable. Despite her often cold and pragmatic demeanor, Gala was deeply devoted to Dalí, and their partnership, though unconventional, was rooted in a mutual understanding and respect that endured throughout their lives.

Gala, who had a daughter named Cécile with Éluard, virtually abandoned her after leaving him for Dalí. Throughout her life, Gala maintained a distant relationship with Cécile, to the point of not recognizing her as her daughter. This estrangement reflected Gala’s focus on her new life with Dalí and her relentless pursuit of personal freedom, often at the expense of past relationships.

Even after marrying Dalí in a civil ceremony in Paris in 1934, Gala's sexual independence continued. She had numerous affairs with younger men, often with Dalí’s encouragement. Dalí, who harbored complex voyeuristic tendencies, not only accepted but sometimes facilitated these liaisons, seeing them as an extension of Gala’s role as his muse and a source of his creative inspiration. This dynamic, while unconventional, was a central aspect of their relationship, demonstrating the surreal blend of love, art, and sexuality that defined their lives together.

In 1934, Dalí and Gala married, formalizing a partnership that had already become the cornerstone of Dalí's personal and professional life. Gala managed many aspects of Dalí's career, helping him navigate the art world and ensuring his works reached a global audience. This partnership proved crucial during their years in the United States during World War II, where Gala's business acumen helped Dalí expand his influence beyond painting into areas like film and fashion.

By the time they returned to Spain in 1948, Dalí had become one of the most famous and controversial artists in the world, with Gala remaining a constant and guiding presence in his life. Her influence, both as a muse and a manager, had shaped Dalí's work and career in ways that would leave an indelible mark on the history of art.

-1.png?width=527&height=527&name=Untitled%20design%20(2)-1.png)